Friday, 28 April 2023

It’s already two years since I last looked at KDE git history. As I decribed in the latest edition, this is inspired by the work of Hans Petter Jansson for GNOME and use the tool he made (fornalder).

fornalder is a formidable tool. It is easy to use and the documentation in the readme is great. I don’t know if this is because it was programmed in Rust but fornalder was also blazingly fast and most of the time spent during this analysis was spent on cloning the repos.

These stats include all the extragear, plasma, frameworks and release service repository as well as most of the KDE websites and a few KDE playground projects I had on my hard drive. For example, it doesn’t includes most of the unmaintained projects (e.g. kdepimlibs, koffice, plasma-mediacenter, …). Also important to note, is that this doesn’t include translations at all, since they are stored in SVN and added in the git repository with a script which remove authorship information.

I also removed manually all the scripted commits and I merged the contributions from “Laurent Montel” with “Montel Laurent” as well as the one from various contributors whose name changed.

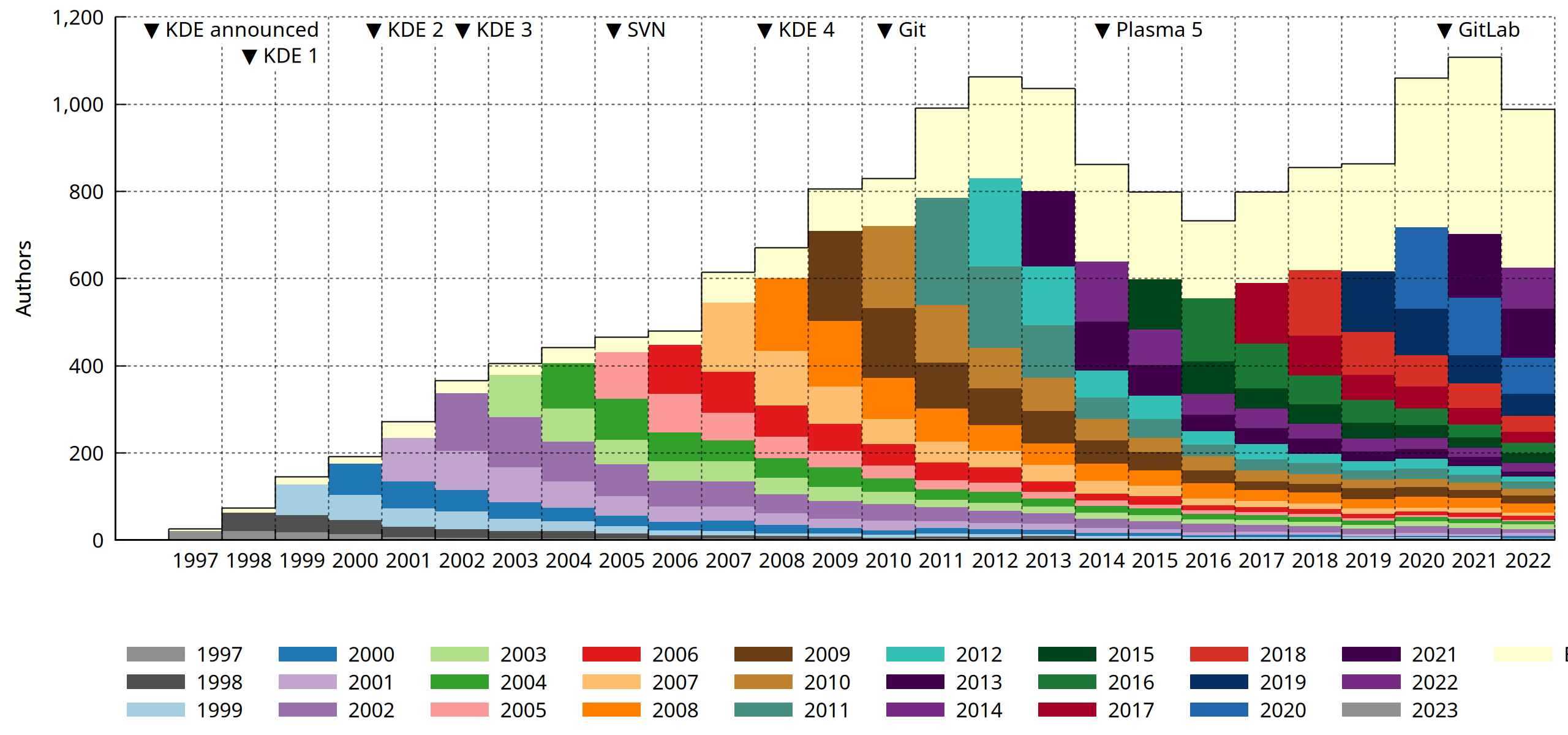

Active Contributors

The explaination for the colors is described by Hans Petter Janssson in his blog post by:

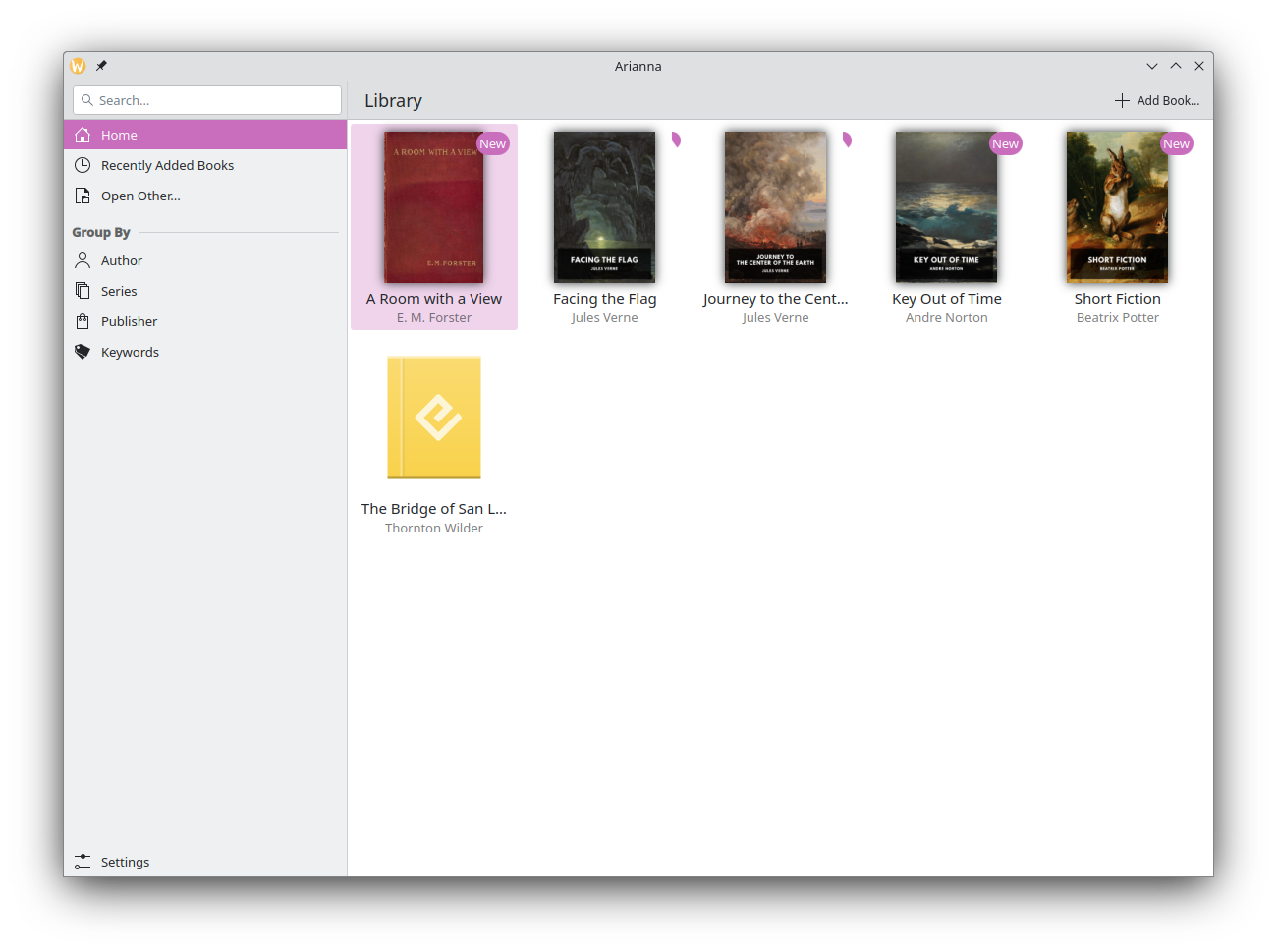

The stacked histogram above shows the number of contributors who touched the project on a yearly basis. Each contributor is assigned to a generational cohort based on the year of their first contribution. The cohorts tend to shrink over time as people leave.

There’s a special “drive-by” cohort (in a fetching shade of off-white) for contributors who were only briefly involved, meaning all their activity fits in a three-month window. It’s a big group. In a typical year, it numbers 200-400 persons who were not seen before or since. Most of them contribute a single commit.

In 2022, the number of active decreased slightly compared to 2021 and 2020, which might be due to the fact that the pandemic ended and people spend less time on their PC contributing to open source projects (which provided an huge boost in 2019/2020).

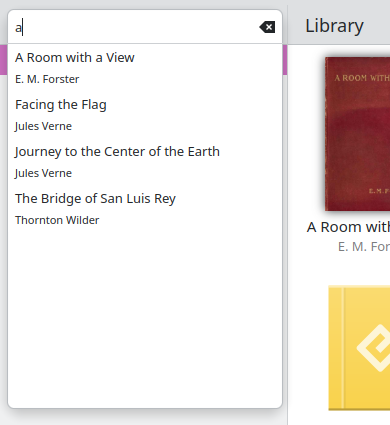

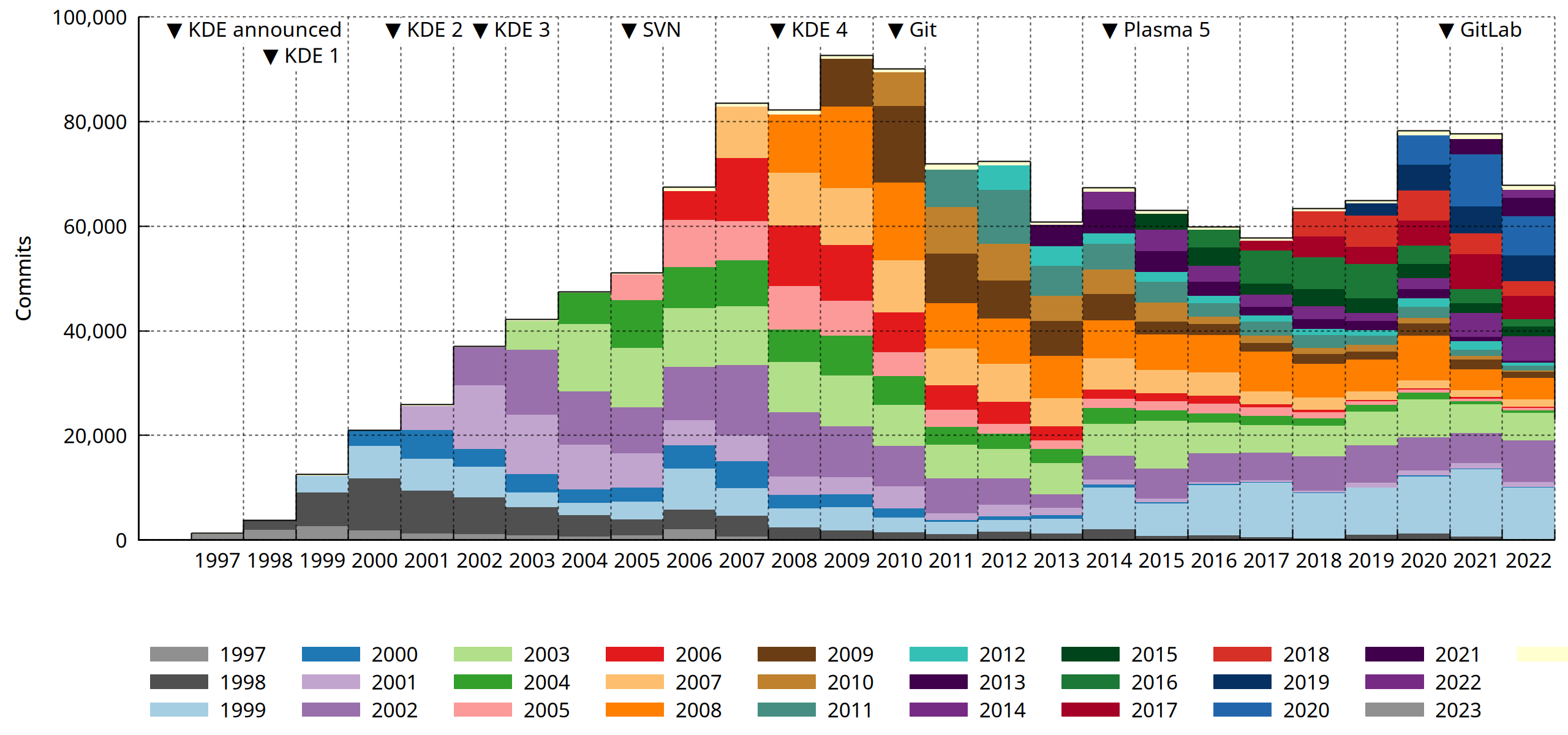

Commits Count

In 2022, the number of commits decreased as well, which can be attributed to the smaller number of overall contributors and a bit less activity from some long time contributors.

But I would not worry too much about these numbers as we are still above the 2019 level (pre-gitlab and pandemic) and looking already at the numbers for the first few months of 2023 it’s increasing again.

Conclusion

I would say that KDE is in relatively good health. This is particularly impressive for a project with little corporate backing and with mostly volunteers.

In 2023, we are also finalizing the transition to Qt6 and KF6 with a first release of KF6 and Plasma 6 around the end of this year, begining of next year.

There is no better time to get involved or to consider making a donation!

You can play with raw data in the form of a sqlite dabase (>200Mb)

CarlSchwan

CarlSchwan

piyushaggarwal:kde.org

piyushaggarwal:kde.org