I would like to show the evolution of one function in rolisteam code.

This function is called when the user (Game Master) closes a map or image.

The function must close the map or image and send a network order to each player to close the image or plan.

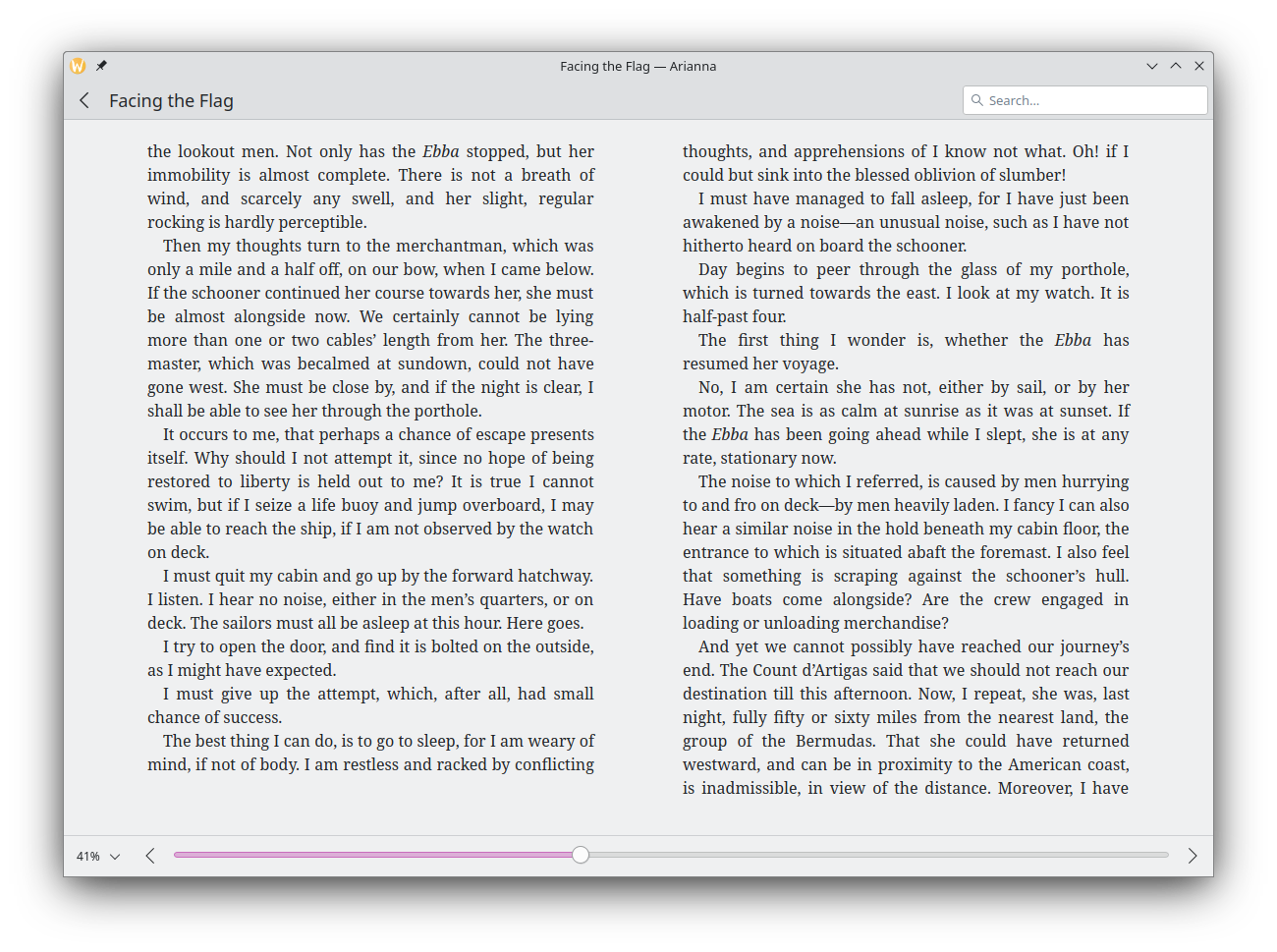

At the beginning, the function looked like that.

Some code line and comments were written in French. No coding rules were respected.

Low-level code for networking. The function was very long.

[pastacode lang=”cpp” message=”” highlight=”” provider=”manual” manual=”%20%2F%2F%20On%20recupere%20la%20fenetre%20active%20(qui%20est%20forcement%20de%20type%20CarteFenetre%20ou%20Image%2C%20sans%20quoi%20l’action%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20ne%20serait%20pas%20dispo%20dans%20le%20menu%20Fichier)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20QWidget%20*active%20%3D%20workspace-%3EactiveWindow()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Ne%20devrait%20jamais%20arriver%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if%20(!active)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20qWarning(%22Close%20map%20action%20called%20when%20no%20widget%20is%20active%20in%20the%20workspace%20(fermerPlanOuImage%20-%20MainWindow.h)%22)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20return%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20On%20verifie%20pour%20le%20principe%20qu’il%20s’agit%20bien%20d’une%20CarteFenetre%20ou%20d’une%20Image%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if%20(active-%3EobjectName()%20!%3D%20%22CarteFenetre%22%20%26%26%20active-%3EobjectName()%20!%3D%20%22Image%22)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20qWarning(%22not%20expected%20type%20of%20windows%20(fermerPlanOuImage%20-%20MainWindow.h)%22)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20return%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Creation%20de%20la%20boite%20d’alerte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20QMessageBox%20msgBox(this)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.addButton(QMessageBox%3A%3AYes)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.addButton(QMessageBox%3A%3ACancel)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setIcon(QMessageBox%3A%3AInformation)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.move(QPoint(width()%2F2%2C%20height()%2F2)%20%2B%20QPoint(-100%2C%20-50))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20On%20supprime%20l’icone%20de%20la%20barre%20de%20titre%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20Qt%3A%3AWindowFlags%20flags%20%3D%20msgBox.windowFlags()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowFlags(flags%20%5E%20Qt%3A%3AWindowSystemMenuHint)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20M.a.j%20du%20titre%20et%20du%20message%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if%20(active-%3EobjectName()%20%3D%3D%20%22CarteFenetre%22)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowTitle(tr(%22Close%20Map%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setText(tr(%22Do%20you%20want%20to%20close%20this%20map%3F%5CnIt%20will%20be%20closed%20for%20everybody%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20else%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowTitle(tr(%22Close%20Picture%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setText(tr(%22Do%20you%20want%20to%20close%20this%20picture%3F%5CnIt%20will%20be%20closed%20for%20everybody%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.exec()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Si%20l’utilisateur%20n’a%20pas%20clique%20sur%20%22Fermer%22%2C%20on%20quitte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if%20(msgBox.result()%20!%3D%20QMessageBox%3A%3AYesRole)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20return%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Emission%20de%20la%20demande%20de%20fermeture%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if%20(active-%3EobjectName()%20%3D%3D%20%22CarteFenetre%22)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Recuperation%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20QString%20idCarte%20%3D%20((CarteFenetre%20*)active)-%3Ecarte()-%3EidentifiantCarte()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Taille%20des%20donnees%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20quint32%20tailleCorps%20%3D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Taille%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20sizeof(quint8)%20%2B%20idCarte.size()*sizeof(QChar)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Buffer%20d’emission%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20char%20*donnees%20%3D%20new%20char%5BtailleCorps%20%2B%20sizeof(enteteMessage)%5D%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Creation%20de%20l’entete%20du%20message%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20enteteMessage%20*uneEntete%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete%20%3D%20(enteteMessage%20*)%20donnees%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3Ecategorie%20%3D%20plan%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3Eaction%20%3D%20fermerPlan%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3EtailleDonnees%20%3D%20tailleCorps%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Creation%20du%20corps%20du%20message%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20int%20p%20%3D%20sizeof(enteteMessage)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Ajout%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20quint8%20tailleIdCarte%20%3D%20idCarte.size()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20memcpy(%26(donnees%5Bp%5D)%2C%20%26tailleIdCarte%2C%20sizeof(quint8))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20p%2B%3Dsizeof(quint8)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20memcpy(%26(donnees%5Bp%5D)%2C%20idCarte.data()%2C%20tailleIdCarte*sizeof(QChar))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20p%2B%3DtailleIdCarte*sizeof(QChar)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Emission%20de%20la%20demande%20de%20fermeture%20de%20la%20carte%20au%20serveur%20ou%20a%20l’ensemble%20des%20clients%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20emettre(donnees%2C%20tailleCorps%20%2B%20sizeof(enteteMessage))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Liberation%20du%20buffer%20d’emission%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20delete%5B%5D%20donnees%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Suppression%20de%20la%20CarteFenetre%20et%20de%20l’action%20associee%20sur%20l’ordinateur%20local%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20((CarteFenetre%20*)active)-%3E~CarteFenetre()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Emission%20de%20la%20demande%20de%20fermeture%20de%20l’image%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20else%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Recuperation%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20QString%20idImage%20%3D%20((Image%20*)active)-%3EidentifiantImage()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Taille%20des%20donnees%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20quint32%20tailleCorps%20%3D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Taille%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20sizeof(quint8)%20%2B%20idImage.size()*sizeof(QChar)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Buffer%20d’emission%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20char%20*donnees%20%3D%20new%20char%5BtailleCorps%20%2B%20sizeof(enteteMessage)%5D%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Creation%20de%20l’entete%20du%20message%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20enteteMessage%20*uneEntete%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete%20%3D%20(enteteMessage%20*)%20donnees%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3Ecategorie%20%3D%20image%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3Eaction%20%3D%20fermerImage%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20uneEntete-%3EtailleDonnees%20%3D%20tailleCorps%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Creation%20du%20corps%20du%20message%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20int%20p%20%3D%20sizeof(enteteMessage)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Ajout%20de%20l’identifiant%20de%20la%20carte%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20quint8%20tailleIdImage%20%3D%20idImage.size()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20memcpy(%26(donnees%5Bp%5D)%2C%20%26tailleIdImage%2C%20sizeof(quint8))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20p%2B%3Dsizeof(quint8)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20memcpy(%26(donnees%5Bp%5D)%2C%20idImage.data()%2C%20tailleIdImage*sizeof(QChar))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20p%2B%3DtailleIdImage*sizeof(QChar)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Emission%20de%20la%20demande%20de%20fermeture%20de%20l’image%20au%20serveur%20ou%20a%20l’ensemble%20des%20clients%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20emettre(donnees%2C%20tailleCorps%20%2B%20sizeof(enteteMessage))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Liberation%20du%20buffer%20d’emission%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20delete%5B%5D%20donnees%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%2F%2F%20Suppression%20de%20l’Image%20et%20de%20l’action%20associee%20sur%20l’ordinateur%20local%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20((Image%20*)active)-%3E~Image()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D”/]

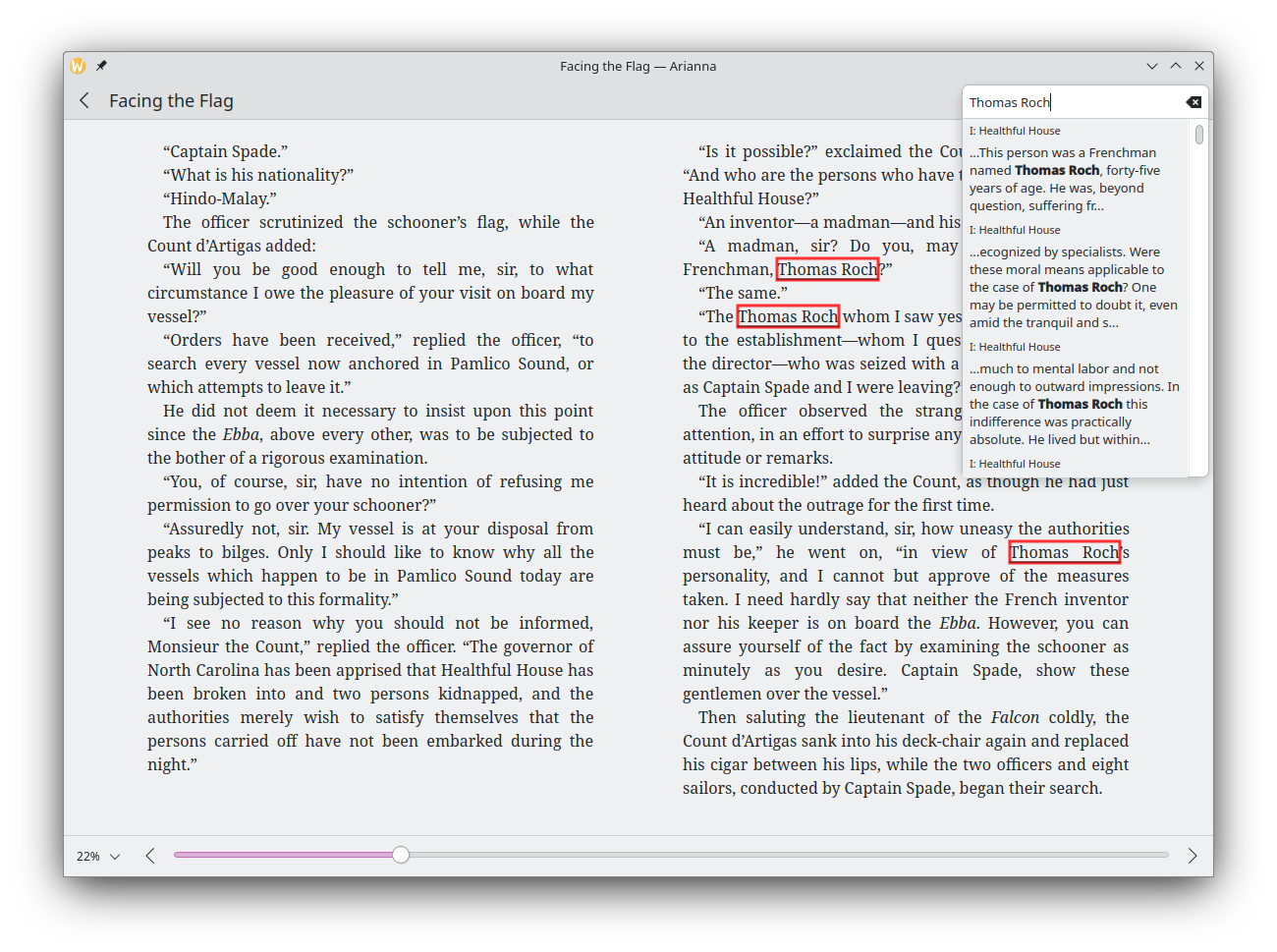

A big step forward, the networking code has been reworked.

So the readability is improved. It is also possible to see the beginning of polymorphism. MediaContener is used but not everywhere.

[pastacode lang=”cpp” message=”Version Intermédiaire” highlight=”” provider=”manual” manual=”QMdiSubWindow*%20subactive%20%3D%20m_mdiArea-%3EcurrentSubWindow()%3B%0AQWidget*%20active%20%3D%20subactive%3B%0AMapFrame*%20bipMapWindow%20%3D%20NULL%3B%0A%0Aif%20(NULL!%3Dactive)%0A%7B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20QAction*%20action%3DNULL%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20Image*%20%20imageFenetre%20%3D%20dynamic_cast(active)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20QString%20mapImageId%3B%0A%20%20%20%20QString%20mapImageTitle%3B%0A%20%20%20%20mapImageTitle%20%3D%20active-%3EwindowTitle()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20bool%20image%3Dfalse%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%2F%2Fit%20is%20image%0A%20%20%20%20if(NULL!%3DimageFenetre)%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20m_pictureList.removeOne(imageFenetre)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20mapImageId%20%3D%20imageFenetre-%3EgetMediaId()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20image%20%3D%20true%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20action%20%3D%20imageFenetre-%3EgetAction()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20else%2F%2Fit%20is%20a%20map%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20bipMapWindow%3D%20dynamic_cast(active)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if(NULL!%3DbipMapWindow)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20mapImageId%20%3D%20bipMapWindow-%3EgetMediaId()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20action%20%3D%20bipMapWindow-%3EgetAction()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20else%2F%2F%20it%20is%20undefined%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20return%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20QMessageBox%20msgBox(this)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.setStandardButtons(QMessageBox%3A%3AYes%20%7C%20QMessageBox%3A%3ACancel%20)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.setDefaultButton(QMessageBox%3A%3ACancel)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.setIcon(QMessageBox%3A%3AInformation)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.move(QPoint(width()%2F2%2C%20height()%2F2)%20%2B%20QPoint(-100%2C%20-50))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20Qt%3A%3AWindowFlags%20flags%20%3D%20msgBox.windowFlags()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowFlags(flags%20%5E%20Qt%3A%3AWindowSystemMenuHint)%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20if%20(!image)%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowTitle(tr(%22Close%20Map%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20else%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msgBox.setWindowTitle(tr(%22Close%20Picture%22))%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.setText(tr(%22Do%20you%20want%20to%20close%20%251%20%252%3F%5CnIt%20will%20be%20closed%20for%20everybody%22).arg(mapImageTitle).arg(image%3Ftr(%22%22)%3Atr(%22(Map)%22)))%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20msgBox.exec()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20if%20(msgBox.result()%20!%3D%20QMessageBox%3A%3AYes)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20return%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20if%20(!image)%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20NetworkMessageWriter%20msg(NetMsg%3A%3AMapCategory%2CNetMsg%3A%3ACloseMap)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msg.string8(mapImageId)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msg.sendAll()%3B%0A%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20m_mapWindowMap.remove(mapImageId)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20m_playersListWidget-%3Emodel()-%3EchangeMap(NULL)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20m_toolBar-%3EchangeMap(NULL)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20else%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20NetworkMessageWriter%20msg(NetMsg%3A%3APictureCategory%2CNetMsg%3A%3ADelPictureAction)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msg.string8(mapImageId)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20msg.sendAll()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20MediaContainer*%20%20mediaContener%20%3D%20dynamic_cast(subactive)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20if(NULL!%3DmediaContener)%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20CleverURI*%20cluri%20%3D%20mediaContener-%3EgetCleverUri()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20cluri-%3EsetDisplayed(false)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if(NULL!%3Dm_sessionManager)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20m_sessionManager-%3EupdateCleverUri(cluri)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%0A%20%20%20%20delete%20action%3B%0A%20%20%20%20delete%20subactive%3B%0A%7D%0A”/]

Then, we implements a solution to describe map, vmap (v1.8) or image as mediacontener.

They share a large part of their code, so it becomes really easy to do it.

[pastacode lang=”cpp” message=”Actuel” highlight=”” provider=”manual” manual=”QMdiSubWindow*%20subactive%20%3D%20m_mdiArea-%3EcurrentSubWindow()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20MediaContainer*%20container%20%3D%20dynamic_cast(subactive)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20if(NULL%20!%3D%20container)%0A%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20CleverURI%3A%3AContentType%20type%20%3D%20container-%3EgetContentType()%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20if(CleverURI%3A%3AVMAP%20%3D%3D%20type)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20removeVMapFromId(container-%3EgetMediaId())%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20else%20if(CleverURI%3A%3AMAP%20%3D%3D%20type)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20removeMapFromId(container-%3EgetMediaId())%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20else%20if(CleverURI%3A%3APICTURE%20%3D%3D%20type%20)%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20removePictureFromId(container-%3EgetMediaId())%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%20%20%7D%0A”/]

CarlSchwan

CarlSchwan

albertvaka

albertvaka

@k3ys:matrix.org

@k3ys:matrix.org