This blog post was not easy to write as it started as a very simple thing intended for developers, but later, when I was digging around, it turned out that there is no good single resource online on copyright statements. So I decided to take this stab at writing one.

I tried to strike a good balance between 1) keeping it short and to the point for developers who just want to know what to do, and 2) FOSS compliance officers and legal geeks who want to understand not just best practices, but also the reasons behind them.

If you are extremely short on time, the TL;DR should give you the bare minimal instructions, but if you have just 2 minutes I would advise you to read the actual HowTo a bit lower below.

Of course, if you have about 20 minutes of time, the best way is always to start reading at the beginning and finish at the end.

Where else to find this article & updates

A copy of this blog is available also on Liferay Blog.

Haksung Jang (장학성) was awesome enough to publish a Korean translation.

2021-03-09 update: better wording; more info on how to handle anonymous authors and when copyright is held by employer, © and ASCII, multiple authors; DCO; easier REUSE instructions

2022-10-23 update: more FAQ entries

2023-03-28 update: a few more FAQ entries following feedback at FOSDEM and from Mastodon

TL;DR

Use the following format:

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © {$year_of_file_creation} {$name_of_copyright_holder} <{$contact}>

SPDX-License-Identifier: {$SPDX_license_name}

… put that in every source code file and go check out (and follow) REUSE.software best practices, published by the FSFE.

E.g. for a file that I created today and I released under the BSD-3-Clause license, I would use put the following as a comment at the top of the source code file:

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © 2020 Matija Šuklje <matija@suklje.name>

SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

Introduction and copyright basics

Copyright is automatic (since the Berne convention) and any work of authorship is automatically protected by it – essentially giving the copyright holder exclusive power over their work. In order for your downstream to have the rights to use any of your work – be that code, text, images or other media – you need to give them a license to your work.

So in order for you to copy, implement, modify etc. the code from others, you need to be given the needed rights – i.e. a license –, or make use of a statutory limitation or exception. And if that license has some obligations attached, you need to meet them as well.

In any case, you have to meet the basic requirements of copyright law as well. At the very least you need to have the following two in place:

- attribution – list the copyright holders and/or authors – especially in jurisdictions which recognise moral rights (e.g. most of EU) it is important to keep the names of authors, if they are listed;

- license(s) – since a license is the only thing that gives anybody other than the copyright holder themself the right to use the code, you are very well advised to have a notice of the the license and its full text present – this goes for both for your outbound licenses and the inbound licenses you received from others by using 3rd party works, such as copied code or libraries.

Inbound vs. outbound licenses

The license you give to your downstream is called an outbound license, because it handles the rights in the code that flow out of you. In turn that same license in the same work would then be perceived by your downstream as their inbound license, as it handles the rights in the code that flows into them.

In short, licenses describing rights flowing in are called inbound licenses, and the licenses describing rights flowing out are called outbound licenses.

The good news is that attribution is a discretionary right that can be exercised by the author should they choose to. And you are obliged to keep the attribution notices only insofar as the author(s) made use of that right. Which means that if the author has not listed themselves, you do not have to hunt them down yourself.

Why have the copyright statement?

Which brings us to the question of whether you need to write your own copyright statement.

First, some very brief history …

The urge to absolutely have to write copyright statements stems from the inertia in the USA, as it only joined the Berne convention in 1989, well after computer programs were a thing. Which means that before then the US copyright law still required an explicit copyright statement in order for a work to be protected.

Copyright statements are useful

The copyright statement is not required by law, but in practice very useful as proof, at best, and indicator, more likely, of what the copyright situation of that work is. This can be very useful for compliance reasons, traceability of the code etc.

Attribution is practically unavoidable, because a) most licenses explicitly call for it, and if that fails b) copyright laws of most jurisdictions require it anyway.

And if that is not enough, then there is also c) sometimes you will want to reach the original author(s) of the code for legal or technical reasons.

So storing both the name and contact information makes sense for when things go wrong. Finding the original upstream of a runaway file you found in your codebase – if there are no names or links in it – is a huge pain and often includes (currently still) expensive specialised software. I would suspect the onus on a FOSS project to be much lower than on a corporation in this case, but still better to put a little effort upfront than having to do some serious archæology later.

How to write a good copyright statement and license notice

Finally we come to the main part of this article!

A good copyright statement should consist of the following information:

- start with the © sign;

- the year of the first publication – a good date would be the year in which you created the file and then do not touch that date anymore;

- the name of the copyright holder – typically the author, but depending on the circumstances might be their employer or if there is a CLA in place the legal entity or person they transferred their rights to;

- a valid contact to the copyright owner

As an example, this is what I would put on something I wrote today:

© 2020 Matija Šuklje <matija@suklje.name>

While you are at it, it would make a lot of sense to also notify everyone which license you are releasing your code under as well. Using an SPDX ID is a great way to unambiguously state the license of your code. (See note mentioned below for an example of how things can go wrong otherwise.)

And if you have already come so far, it is just a small step towards following the best practices as described by REUSE.software by using SPDX tags to make your copyright statement (marked with SPDX-FileCopyrightText) and license notice (marked with SPDX-License-Identifier and followed by an SPDX ID).

Here is now an example of a copyright statement and license notice that check all the above boxes and also complies with both the SPDX and the REUSE.software specifications:

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © 2020 Matija Šuklje <matija@suklje.name>

SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

Now make sure you have these in comments of all your source code files.

Q&A

Over the years, I have heard many questions on this topic – both from developers and lawyers.

I will try to address them below in no particular order.

If you have a question that is not addressed here, do let me know and I will try to include it in an update.

Why keep the year?

Some might argue that for the sake of simplicity it would be much easier to maintain copyright statements if we just skip the years. In fact, that is a policy at Microsoft/GitHub at the time of this writing.

While I agree that not updating the year simplifies things enormously, I do think that keeping a date helps preserve at least a vague timeline in the codebase. As the question is when the work was first expressed in a medium, the earliest date provable is the time when that file was first created.

In addition, having an easy way to find the earliest date of a piece of code, might prove useful also in figuring out when an invention was first expressed to the general public. Something that might become useful for patent defense.

This is also why e.g. in Liferay our new policy is to write the year of the file creation, and then not change the year any more.

Innocent infringement excursion for legal geeks

17 U.S. Code § 401.(d) states that if a work carries a copyright notice in the form that the law prescribes, in a copyright infringement case the defendant cannot rely on the innocent infringement defense, except if they had reason to believe their use was covered fair use. And even then, the innocent infringer would have to be e.g. a non-profit broadcaster or archive to be still eligible to such defence.

So, if you are concerned with copyright violations (at least in USA), you may actually want to make sure your copyright statements include both the copyright sign and year of publication.

See also note in Why the © sign for how a copyright notice following the US copyright act looks like.

Why not bump the year on change?

I am sure you have seen something like this before:

Copyright (C) 1992, 1995, 2000, 2001, 2003 CompanyX Inc.

The presumption behind this is that whenever you add a new year in the copyright statement, the copyright term would start anew, and therefore prolong the time that file would be protected by copyright.

Adding a new year on every change – or, even worse, simply every 1st January – is a practice still too wide-spread even today. Unfortunately, doing this is useless at best, and misleading at worst. Needless to say, if you do this as part of your build process, this is extra wrong. For the origin of this myth see the short history above.

A big problem with this approach is that not every contribution is original or substantial enough to be copyrightable – even the popular 5 (or 10, or X) SLOC rule of thumb is legally-speaking very debatable.

So, in order to keep your copyright statement true, you would need to make a judgement call every time whether the change was substantial and original enough to be granted copyright protection by the law and therefore if the year should be bumped. And that is a substantial test for every time you change a file.

On the other hand copyright lasts at least 50 (and usually 70) years after the death of the author; or if the copyright holder is a legal entity (e.g. CompanyX Inc.), since publication. So the risk of your own copyright expiring under your feet is very very low.

Worst case thought experiment

Let us imagine the worst possible scenario now:

1) you never bump the year in a copyright statement in a file and 2) 50+ years after its initial release, someone copies your code as if it were in public domain. Now, if you would have issue with that and go to court, and 3) the court would (very unlikely) take only the copyright statements in that file into account as the only proof and based on that 4) rule that the code in that file would have fallen under public domain and therefore the FOSS license would not apply to it any more.

The end result would simply be that (in one jurisdiction) that file would fall into public domain and be up for grabs by anyone for anything, no copyright, no copyleft, 50+ years from the file’s creation (instead of e.g. 5, maybe 20 years later).

But, honestly, how likely is it that 50 years from now the same (unaltered) code would still be (commercially) interesting?

… and if it turns out you do need to bump the year eventually, you still have, at worst, 50 years to sort it out – so, ample opportunity to mitigate the risk.

In addition to that, as typically a single source code file is just one of the many cogs in a bigger piece of software, what you are more concerned with is the software product/project as a whole. As the software grows, you will keep adding new files, and those will obviously have newer years in them. So the codebase as a whole work will already include copyright statements with newer years in it anyway.

Keep the Git/VCS history clean

Also, bumping the year in all the files every year messes with the usefulness of the Git/VCS history, and makes the log unnecessarily long(er) and the repository consumes more space.

It makes all the files seem equally old (in years), which makes it hard to identify stale code if you are looking for it.

Another issue might be that your year-bumping script can be too trigger-happy and bump the years also in the files that do not even belong to you. Furthering misinformation both in your VCS and the files’ copyright notices.

Do not bump the year during build time

Bumping the year manually is bad, but automating year bumping during build time is taking it to another level!

One could argue – and I suspect this is where it originates from – that since compiling is translation and as such an exclusive right of the copyright holder. But while translation from one programming language to another clearly can take a lot of mental effort and might require different ways how to express something, a machine-compilation from human-readable source code to machine-readable object/binary code per se is extremely unlikely to have added a new copyrightable component into the mix. That would be like saying an old song would gain new copyright just because it was released in a new audio format without any other changes.

Bumping the year during build time also messes up reproducible builds.

Why not use a year range?

Similar to the previous question, the year span (e.g. 1990-2013) is basically just a lazy version of bumping the year. So all of the above-mentioned applies.

A special case is when people use a range like {$year}-present. This has almost all of the above-mentioned issues, plus it adds another dimension of confusion, because what constitutes the “present” is an open – and potentially philosophical – question. Does it mean:

- the time when the file was last modified?

- the time it was released as a package?

- the time you downloaded it (maybe for the first time)?

- the time you ran it the last time?

- or perhaps even the ever eluding “right now”?

As you can see, this does not help much at all. Quite the opposite!

But doesn’t Git/Mercurial keep a better track?

Not reliably.

Git (and other VCS) are good at storing metadata, but you should be careful about it.

Git does have an Author field, which is separate from the Committer field. But even if we were to assume – and that is a big assumption – Git’s Author was the actual author of the code committed, they may not be the copyright holder.

Furthermore, the way git blame and git diff currently work, is line-by-line and using the last change as the final author, making Git suboptimal for finding out who actually wrote what.

Token-based blame information

For a more fine-grained tool to see who to blame for which piece of code, check out cregit.

And ultimately – and most importantly – as soon as the file(s) leave the repository, the metadata is lost. Whether it is released as a tarball, the repository is forked and/or rebased, or a single file is simply copied into a new codebase, the trace is lost.

All of these issues are addressed by simply including the copyright statement and license information in every file. REUSE.software best practices handle this very well.

Why the © sign?

Some might argue that the English word “Copyright” is so common nowadays that everyone understands it, but if you actually read the copyright laws out there, you will find that using © (i.e. the copyright sign) is the only way to write a copyright statement that is common in copyright laws around the world.

Using the © sign makes sense, as it is the the common global denominator.

Comparison between US and Slovenian copyright statements

As an EU example, the Slovenian ZASP §175.(1) simply states that holders of exclusive author’s rights may mark their works with a (c)/© sign in front of their name or firm and year of first publication, which can be simply put as:

© {$year_of_first_publication} {$name_of_author_or_other_copyright_holder}

On the other side of the pond, in the USA, 17 U.S. Code § 401.(b) uses more words to give a more varied approach, and relevant for this question in §401(b)(1) prescribes the use of

the symbol © (the letter C in a circle), or the word “Copyright”, or the abbreviation “Copr.”;

The rest you can go read yourself, but can be summarised as:

(©|Copyright|Copr.) {$year_of_first_publication} {$name_or_abreviation_of_copyright_holder}

See also the note in Why keep the year for why this can matter in front of USA courts.

While the © sign is a pet peeve of mine, from the practical point of view, this is the least important point here. As we established in the introduction, copyright is automatic, so the actual risk of not following the law by its letter is pretty low if you write e.g. “Copyright” instead.

© sign and ASCII

While Unicode (UTF-8, UTF-16, …) is pretty much ubiquitous nowadays, there are places and reasons for when the encoding of source code will have to be limited to a much simpler one, such as ASCII. This could be e.g. in case when the code is written to be put into small embedded devices where every bit counts.

The © character was introduced in 8-bit extended ASCII, but the original 7-bit ASCII does not have it.

So if this is the situation you are in, it is fine to either ommit the copyright sign or replace it with e.g. (C) or Copyright.

A contact is in no way required by copyright law, but from practical reasons can be extremely useful.

It can happen that you need to access the author and/or copyright holder of the code for legal or technical question. Perhaps you need to ask how the code works, or have a fix you want to send their way. Perhaps you found a licensing issue and want to help them fix it (or ask for a separate license). In all of these cases, having a contact helps a lot.

As pretty much all of internet still hinges on the e-mail, the copyright holder’s e-mail address should be the first option. But anything really goes, as long as that contact is easily accessible and actually in use long-term.

Avoiding orphan works

For the legal geeks out there, a contact to the copyright holder mitigates the issue of orphan works.

What if there are many authors or copyright is held by a legal entity?

There will be cases where the authorship will be very dispersed or lie with a legal entity instead. In those cases, it might be more sense to provide a URL to either the project’s or legal entity’s homepage and provide useful information there. If a project lists copyright holders in a file such as AUTHORS or CONTRIBUTORS.markdown a permalink to that file (in the master) of the publicly available repository could also be a good URL option.

How to handle multitudes of authors?

Here are two examples of what you can write in case the project (e.g. Project X) has many authors and does not have a CAA or exclusive CLA in place to aggregate the copyright in a single entity:

© 2010 The Project X Authors <https://projectx.example/about/authors>

© 1998 Contributors to the Project X <https://git.projectx.example/ProjectX/blob/master/CONTRIBUTORS.markdown>

An an example of when the project is handled by a non-profit NGO legal entity.

© 2020 BestProjectNGO <https://bestprojectngo.example>

Bot to automate contributions

A really interesting project is All Contributors, which specifies how to manage contributions to all – even non-code – contributions to a project. It also includes a CLI tool and offers a GitHub bot to automate this process.

The major downside is that the prescribed format is an HTML table embedded in MarkDown. So not very easy to read or parse in source form.

What if I added code to an existing project?

A major benefit of FOSS is that people collaborate on the same project, so it is inevitable that several people will be touching the same file. If that file already includes a copyright statement, this is a good question.

If there are only a handful of people who wrote that file, it would be fine to just add a new line with your copyright statement, as such:

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © 2018 Matija Šuklje <matija@suklje.name>

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © 2021 Master Hacker <mh@example.org>

But if there are many authors that would need to be added that way, to avoid clutter, it would make sense to instead create an AUTHORS.* or CONTRIBUTORS.* file as described in the question above.

What about public domain?

Public domain is tricky.

In general the public domain are works to which the copyright term has expired.

While in some jurisdictions (e.g. USA, UK) you can actually waive your copyright and dedicate your work to public domain, in most jurisdiction (e.g. most of EU member countries) that is not possible.

Which means that depending on the applicable jurisdiction, it may be that although an author wrote that they dedicate their work into public domain this does not meet the legal standard for it to actually happen – they retain the copyright in their own work.

Unsurprisingly, FOSS compliance officers and other people/projects who take copyright and licensing seriously are typically very wary of statements like “this is public domain”.

This can be mitigated in two ways:

- instead of some generic wording, when you want to dedicate something to public domain use a tried and tested public copyright waiver / public domain dedication with a very permissive license, such as 0BSD for code or CC0-1.0 for non-code; and

- include your name and contact if you are the author in the

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: field – 1) because in doubt that will associate you with your dedication to the public domain, and 2) in case anything is unclear, people have a contact to you.

This makes sense to do even for files that you deem are not copyrightable, such as config files – if you mark them as above, everyone will know that you will not exercise your author’s rights (if they existed) in those files.

It may seem a bit of a hassle for something you just released to the public to use however they see fit, without people having to ask you for permission. I get that, I truly do! But do consider that if you already put so much effort into making this wonderful stuff you and donating it to the general humanity, it would be a huge pity that, for (silly) legal details, in the end people would not (be able to) use it at all.

What about minified JS?

Modern code minifiers/uglifiers tend to have an optional flag to preserve copyright and licensing info, even when they rip out all the other comments.

The copyright does not simply go away if you minify/uglify the code, so do make sure that you use a minifier that preserves both the copyright statement as well as the license (at least its SPDX Identifier) – or better yet, the whole REUSE-compliant header.

Transformations of code

Translations between different languages, compilations and other transformations are all exclusive rights of the copyright owner. So you need a valid license even for compiling and minifying.

What is wrong with “All rights reserved”?

Often you will see “all rights reserved” in copyright statements even in a FOSS project.

The cause of this, I suspect, lies again from a copycat behaviour where people tend to simply copy what they so often found on a (music) CD or in a book. Again, the copyright law does not ask for this, even if you want to follow the fullest formal copyright statement rules.

But what it does bring, is confusion.

The statement “all rights reserved” obviously contradicts the FOSS license the same file is released under. The latter gives everyone the rights to use, study, share and improve the code, while the former states that all of these rights the author reserves to themself.

So, as those three words cause a contradiction, and do not bring anything useful to the table in the first place, you should not write them in vain.

Practical example

Imagine a FOSS project that has a copy of the MIT license stored in its LICENSE file and (only) the following comment at the top of all its source code files:

# This file is Copyright (C) 1997 Master Hacker, all rights reserved.

Now imagine that someone simply copies one file from that repository/archive into their own work, which is under the AGPL-3.0-only license, and this is also what it says in the LICENSE file in the root of its own repository. And you, in turn, are using this second person’s codebase.

According to the information you have at hand:

- the copyright in the copied file is held by Master Hacker;

- apparently, Mr Hacker reserves all the rights they have under copyright law;

- if you felt like taking a risk, you could assume that the copied file is under the AGPL-3.0-or-later license – which is false, and could lead to copyright violation;

- if you wanted to play it safe, you could assume that you have no valid license to this file, so you decide to remove it and work around it – again false and much more work, but safe;

- you could wait until 2067 and hope this actually falls under public domain by then – but who has time for that.

This example highlights both how problematic the wording of “all rights reserved” can be even if there is a license text somewhere in the codebase.

This can be avoided by using a sane copyright statement (as described in this blog post) and including an unambiguous license ID. REUSE.software ties both of these together in an easy to follow specification.

What if I work for a company, NGO, university?

In many jurisdictions if you are in an employment relationship (at least full employment), your employer would be the one holding the relevant rights.

If the revelant jurisdiction is Slovenian (as an EU example), ZASP §101 (unofficial English translation) says the following:

(1) When copyright work is created by an employee in the execution of his duties or following the instructions given by his employer (copyright work created in the course of employment), it shall be deemed that the economic rights and other rights of the author to such work are exclusively assigned to the employer for the period of ten years from the completion of the work, unless otherwise provided by contract.

(2) On the expiration of the term mentioned in the foregoing paragraph, the rights mentioned in the foregoing paragraph revert to the employee, however, the employer can claim a new exclusive assignment of these rights, for adequate remuneration.

If the relevant jurisdiction is USA this would fall under “work for hire” and the employer would be the copyright holder of any work their employee makes that are within the scope of their employment. There are also other cases where “work for hire” kicks in, but the sloppy rule of thumb is that if the closer the work’s creation was controlled by the employer/hiring party, the more likely it would be the copyright holder.

In any case, if your contract says you are transferring the rights to your employer or the other party, then they would be the copyright holder (e.g. in USA) or at least the exclusive rights holder (e.g. most of EU).

On a similar note, an author / copyright holder / exclusive right holder can transfer the rights they have to another person by written agreement.

What if I want to stay anonymous?

Whether you want to sign your work with your legal name, a pseudonym or even not at all is your own decision as author.

But do take into consideration that if you want to stay anonymous, you will have a much harder time proving you are the author of that piece of code later. For this reason, it would make sense to release your anonymous code under a “public-domain-like” license such as CC0-1.0 or Unlicense.

In any case, unless you have good reasons not to (e.g. for your personal safety), it would be really useful to use the copyright tag to at least include a contact. In case you want to just use a pseudonym, that should not be much of an issue. But in the case you want to stay anonymous, the contact could be simply the URL to the project’s homepage and instead of your name you could state the name of the project, or leave it empty.

Anonymity and Git

If you are concerned about anonymity, do take into consideration also that Git stores both author and committer data for each commit. Look into how to keep those records in a way that they cannot be linked to you.

My project uses DCO. Does this conflict with it?

Not at all. Quite the opposite!

When signing the DCO 1.1, you state that you are contributing under the license as stated in the file. If the file you contributed (to), includes an SPDX license tag, that supports the DCO.

While signing the DCO typically requires you to use git commit --signoff when you commit, so it stores your agreement with DCO in the repository history, if a file is copied outside that git repository that information, along with your authorship information is lost. So it makes sense to include your copyright statement and contact in each file even if you sign a DCO.

How do I find out the date of file creation?

If you are creating a new file, this is trivial, as you just need to enter the current year (e.g. with date +Y).

But if you are adding your copyright statements to your existing software, that might indeed be a bit more tricky.

Luckily, if your project uses a VCS and all its history is tracked in it, you can find the date of the first commit for each file. If using Git, the following command will output you the year the file was first authored:

git log --follow --format=%as {$path} | tail -n1 | cut -c-4

Failing that, you could check with your filesystem (e.g. for EXT4), but this can be of very questionable quality, if you know the file landed on your disk at a later date, you changed disks etc.

If even that is not a viable possibility, just use your best judgement.

Do legal entities even have right to attribution?

That is a tricky question, and probably depends on the jurisdiction in question.

This analysis tries to answer those questions from the Slovenian jurisdiction.

What about if I merge or split a file or just use a snippet?

In case you copy just a part of a file (assuming that part is copyrightable) into another file, you can put retain/copy its licensing metadata by wrapping its SPDX/REUSE tags between an SPDX-SnippetBegin and an SPDX-SnippetEnd tag. For more details see the Snippet tags format annex of the SPDX specification.

An example would se as follows:

# SPDX-SnippetBegin

# SPDX-FileCopyrightText: © 2020 Matija Šuklje <matija@suklje.name>

# SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

...

import sense

lots_of_cool_code()

...

# SPDX-SnippetEnd

You can use this also when e.g. concattenating different JS files into one.

In any case, unless you are the copyright holder, do not remove or alter other people’s copyright statements. You can always add a new one, if it is needed.

hook out → hat tip to the TODO Group for giving me the push to finally finish this article and Carmen Bianca Bakker, Robbie Morrison, as well as the Legal Network for some very welcome feedback

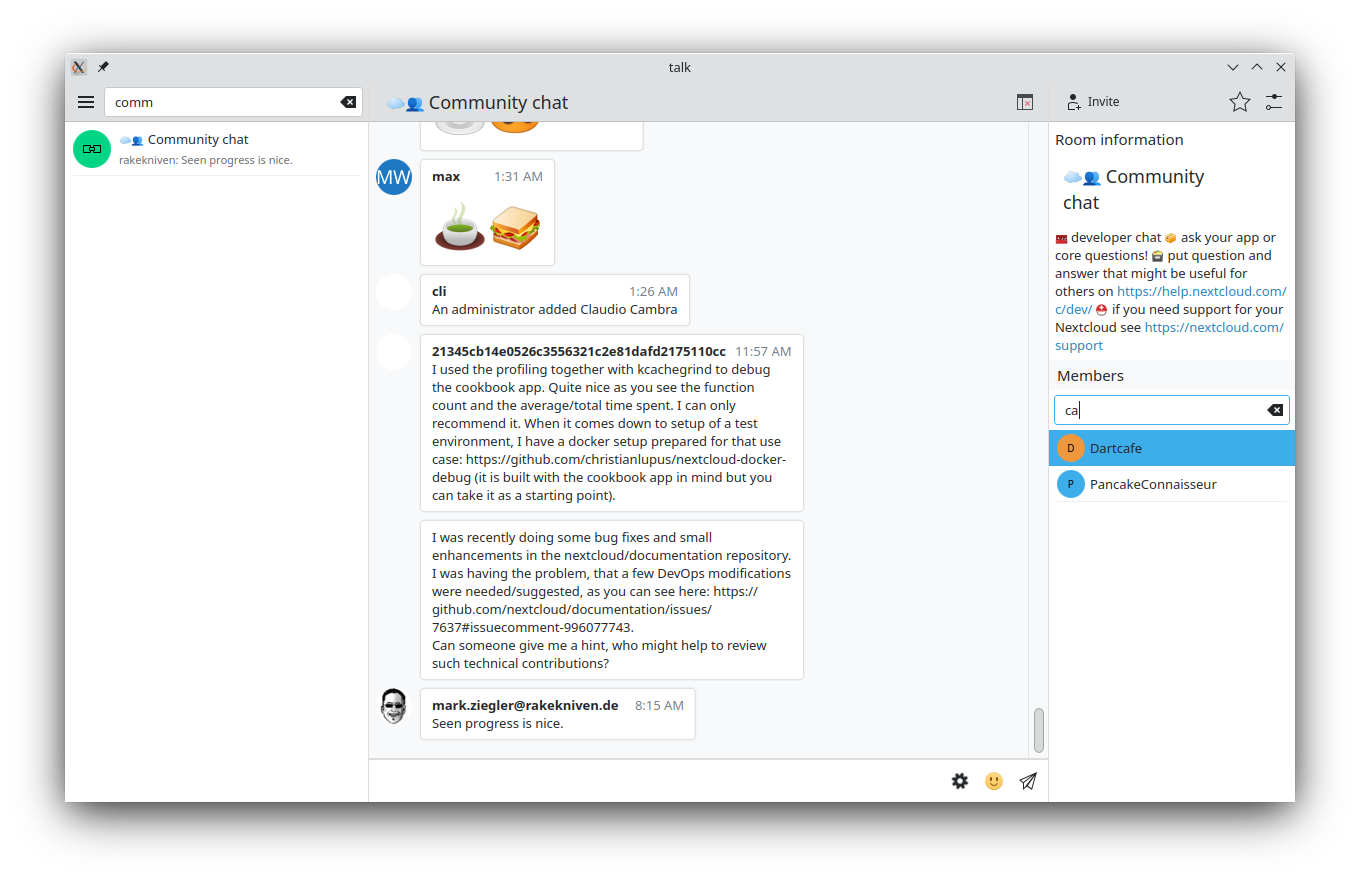

psifidotos

psifidotos

@davidre:kde.org

@davidre:kde.org