Tuesday, 24 February 2026. Today KDE releases a bugfix update to KDE Plasma 6, versioned 6.6.1.

Plasma 6.6 was released in February 2026 with many feature refinements and new modules to complete the desktop experience.

This release adds a week’s worth of new translations and fixes from KDE’s contributors. The bugfixes are typically small but important and include:

View full changelogSunday, 22 February 2026

Overview

The KMyMoney 5.2.2 release contains numerous bug fixes and improvements to enhance stability, usability, and performance of KMyMoney. The focus has been on addressing crashes, improving the user interface, and fixing data handling issues. The source code is available on various mirrors world-wide.

Major Changes and Improvements

Stability Improvements

- Crash Fixes: Multiple crash scenarios have been resolved:

- Fixed crash when closing split view (Bug 514619)

- Fixed crash when closing ledger

- Fixed crash when double clicking schedule group header

- Fixed crash when applying unassigned difference to split (Bug 515690)

- Fixed crash in date entry when data has more than 3 sections (Bug 509701)

- Prevented crash by eliminating lambda slot issues (Bug 510209)

- Prevented infinite recursion in amount edit widget (Bug 513883)

User Interface Enhancements

- Keyboard Navigation:

- Fixed numeric keypad handling when NUMLOCK is off (Bug 507993)

- Fixed handling of numeric keypad decimal separator

- Allow Shift+Return to store a split or transaction

- Allow the equal key to increment the date like the plus key (Bug 507964)

- Start editing transactions only with specific keys

- Editor Improvements:

- Fixed access to tab order editor inside the schedule editor

- Fixed access to tab order editor inside the split editor

- Select payee from completer popup with return key (Bug 516300)

- Focus out on payee widget takes the selected payee from the popup (Bug 508989)

- Use modified values when pressing Return key (Bug 510217)

- Visual Improvements:

- Improved repainting during reconciliation (Bug 514417)

- Reduced ‘jumping’ of ledger view

- Changed method to paint selected ledger items

- Use different background color for transaction and split editor

- Improved column selector

- Use full view size if account view has only one column (Bug 511890)

Reports and Charts

- Report Fixes:

- Fixed bug in reports that date column is shown too small (Bug 507843)

- Fixed pivot reports with transactions in closed accounts (Bug 511553)

- Fixed display of reconciliation report (Bug 507993)

- Fixed handling of data range (Bug 512718)

- Fix handling of tags in reports (Bug 511104)

- Chart Improvements:

- Include limit lines in balance chart (Bug 513754)

- Fixed marker line for credit limits (Bug 513187)

- Show balance and value based on current date

Data Management

- Transaction Handling:

- Don’t clear payee of second split onwards in scheduled tx (Bug 511821)

- Allow changing the memo in multiple transactions at once (Bug 513948)

- Select new investment transaction created by duplication (Bug 513882)

- Fixed generation of payment dates in MyMoneySchedule (Bug 513834)

- Assign an initial payee to each split

- Partial match on payee name in credit transfer

- Fixed removal of splits (Bug 508957)

- Clear the split model before loading another transaction (Bug 509138)

- Search and Filter:

- When searching text in the ledger view also consider split memos (Bug 507851)

- Also search for transaction ID and date in journal filter (Bug 512748)

- Fixed option to hide unused categories (Bug 514445)

- Hide zero accounts in payment account section of home page

Investment Features

- Investment Transaction Editor:

- Fixed price display in investment transaction editor (Bug 507664)

- Update label when security changes (Bug 507664)

- Don’t modify price widget content if not needed (Bug 509454)

- Provide access to zero balance investments even if filtered out

Budget and Schedule Management

- Budget Improvements:

- Allow to modify the budget year when the first fiscal month is january (Bug 515391)

- Set the dirty flag when changing budget name and year (Bug 514221)

- Improved setting of the first day in the fiscal year

- Schedule Features:

- Allow modifying loan schedule using schedule editor (Bug 509029)

- Keep the schedule type for loans (Bug 513387)

- Fixed calculation of number of remaining payments (Bug 509417)

Categories and Accounts

- Allow direct creation of sub-categories (Bug 514987)

- Setup sorting of securities to be locale aware (Bug 508529)

- Keep column settings in institutions view

- Fixed auto increment of check number

Currency and Localization

- The Chilean peso has no fractional part (Bug 286640)

- Support date formats using multiple delimiter characters (Bug 510484)

- Fixed various i18n calls and translation issues

- Replaced unsupported i18n.arg in multiple locations

Online Banking

- Make sure KBanking configuration is stored permanently

- Prevent duplicate generation of KBanking settings code

- Prevent editing online job when no id is present (Bug 512665)

- Show import stats also for Web-Connect imports

Performance Improvements

- Improved file load time

- Improved reconciliation performance

- Don’t update the home page too often

- Prevent starting the transaction editor during filtering (Bug 508288)

- Keep selected ledger items only upon first call (Bug 508980)

Technical Improvements

- Data Integrity:

- Mark file as dirty after modifying user data (Bug 514575)

- Report references of splits to unknown accounts and stop loading

- Use correct method to determine top level parent id (Bug 507416)

- Speedup check if account id references a top-level account group

- Build and Dependencies:

- Fixed build error with Qt 6.10

- Support Qt < 6.8 (Bug 507927)

- Add missing find_package for QtSqlPrivate (Bug 509512)

- Port libical v4 for function name changes

- Port the icalendar plugin to the upcoming libical version 4

- Update flatpak runtime to 6.10

- Various flatpak dependency updates (aqbanking, gwenhywfar, xmlsec, libchipcard)

- Code Quality:

- Prevented variable shadowing

- Resolved compiler warnings

- Fixed various typos

- Removed unused code and header files

- Fixed coverity issues (CID 488310, CID 488368)

VAT Transactions

- Fixed Net→Gross UI update in new transaction editor for VAT transactions (Bug 514180)

- Don’t clear/replace debit/deposit boxes during autofill

Home Page

- Don’t modify running balance when hiding reconciled transactions globally (Bug 508033)

- Fixed display of preferred accounts on home page

- Keep current settings of column selector

Miscellaneous

- Don’t provide defaults that cannot be changed through GUI (Bug 514307)

- Enable QAction before using it (Bug 508081)

- Add option to make ledger filter widget visible permanently

- Use unique style for wizards

- Move the account selector of the ledger view to the left side

- Improved onlinejoboutbox view

- Don’t add the commit hash to tagged versions

- Start transaction editor if action is triggered (Bug 508420)

- Emit signal when returning value from calculator in amount widget (Bug 509135)

- Suppress warning about invalid date in KDateComboBox (Bug 509312)

Bug Fixes by Category

Critical Bugs Fixed

- Bug 507416 – Crash when opening existing database (REOPENED)

- Bug 507843 – Link not working on any report

- Bug 507664 – ‘Total for all shares’ and ‘fraction’ settings ignored when entering investment buy

- Bug 507851 – Text search doesn’t search through transaction’s memo field if written in a single split item

Additional Bug References

Over 50 bugs were addressed in this release. For a complete list, please refer to the KDE Bugzilla.

Installation and Upgrade

Upgrading from 5.2.1

This release is a drop-in replacement for 5.2.1. Simply install the new version and your existing data files will work without modification.

Flatpak Users

The flatpak version has been updated with the latest dependencies and includes home filesystem access permission.

Known Issues

- Bug 507416 (crash when opening existing database) has been reopened and is still under investigation for certain edge cases involving legacy data from Skrooge imports.

Contributors

We would like to thank all contributors who helped make this release possible through code contributions, bug reports, translations, and testing.

Getting Help

- Website: https://www.kmymoney.org

- Support: https://kmymoney.org/support.html

- Bug Reports: https://bugs.kde.org/enter_bug.cgi?product=kmymoney

License

KMyMoney is released under various open source licenses. See the LICENSES folder in the source distribution for details.

Details

A complete description of all changes can be found in the ChangeLog

Saturday, 21 February 2026

Welcome to a new issue of This Week in Plasma!

This week we released Plasma 6.6! So far it’s getting great reviews, even on Phoronix. 😁

As usual, this week the major focus was on triaging bug reports from people upgrading to the new release, and then fixing them. There were a couple of minor regressions as a result of the extensive work done to modernize Plasma widgets’ UI and code for Plasma 6.6, and we’ve already got almost all of them fixed.

In addition to that, feature work and UI improvements roared into focus for Plasma 6.7! Lots of neat stuff this week. Check it all out:

Notable new features

Plasma 6.7.0

While in the Overview effect, you can now switch between virtual desktops by scrolling or pressing the Page Up/Page Down keys! (Kai Uwe Broulik, KDE Bugzilla #453109 and kwin MR #8829)

On Wayland, you can optionally synchronize the stylus pointer with the mouse/touchpad pointer if this fits your stylus usage better. (Joshua Goins, KDE Bugzilla #505663)

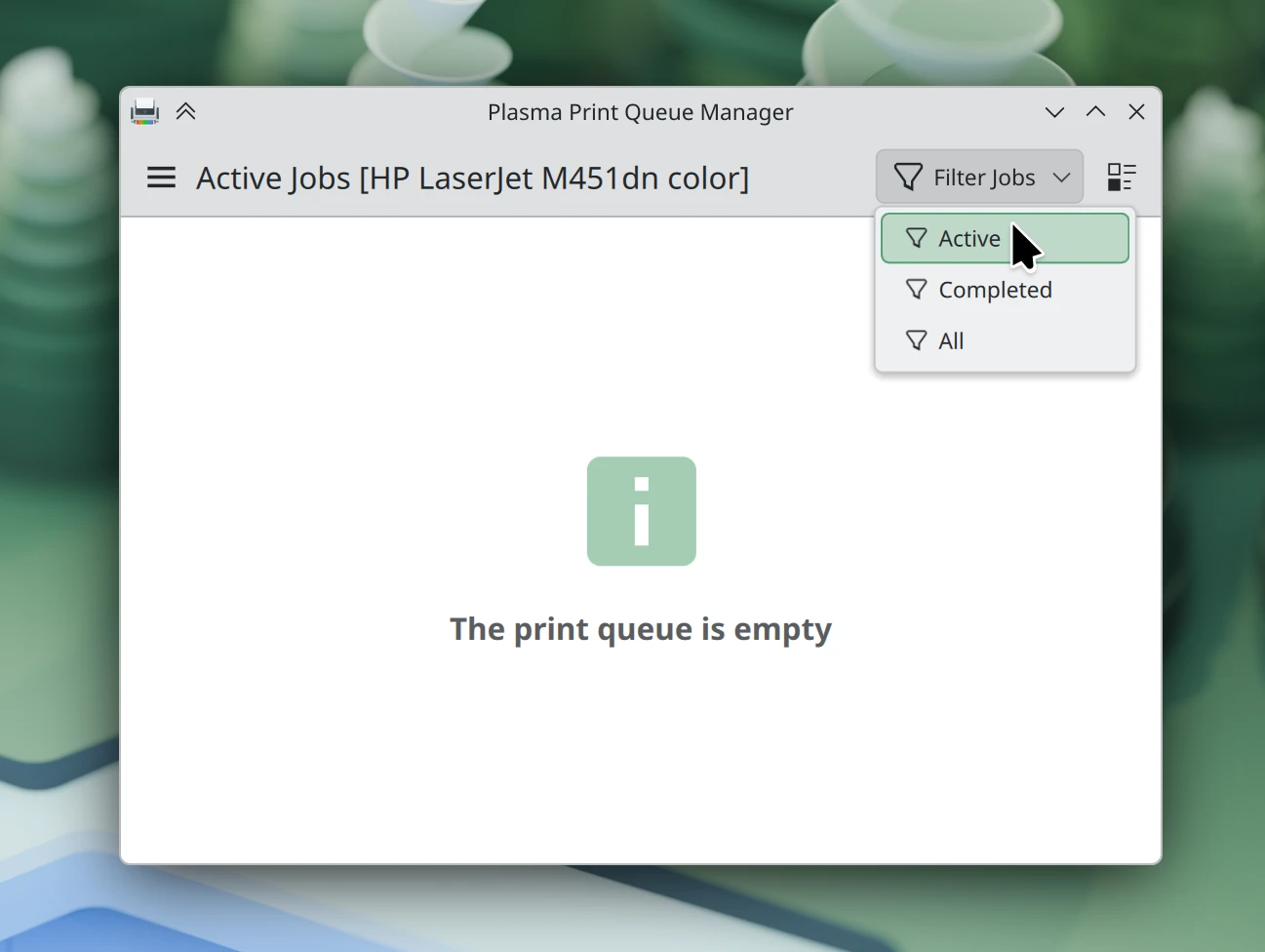

The old print queue dialog has been replaced with a full-featured print queue viewer app, allowing you to visualize multiple queues of multiple printers connected locally or over the network! It still offers a good and normal experience for the common case of having one printer, but now also includes loads of enterprisey features relevant to environments with many printers. (Mike Noe, print-manager MR #280)

You can now exclude windows from screen recording using permanent window rules! (Kai Uwe Broulik, kwin MR #8828)

Added a new --release-capture command-line option to Spectacle that allows invoking it with its “accept screenshot on click-and-release” setting using automation tools. (Arimil, spectacle MR #479)

Notable UI improvements

Plasma 6.6.1

The Custom Tiling feature accessed with Meta+T no longer inappropriately respects key repeat, and therefore no longer becomes practically impossible to open with a very high key repeat rate. (Ritchie Frodomar, KDE Bugzilla #515940)

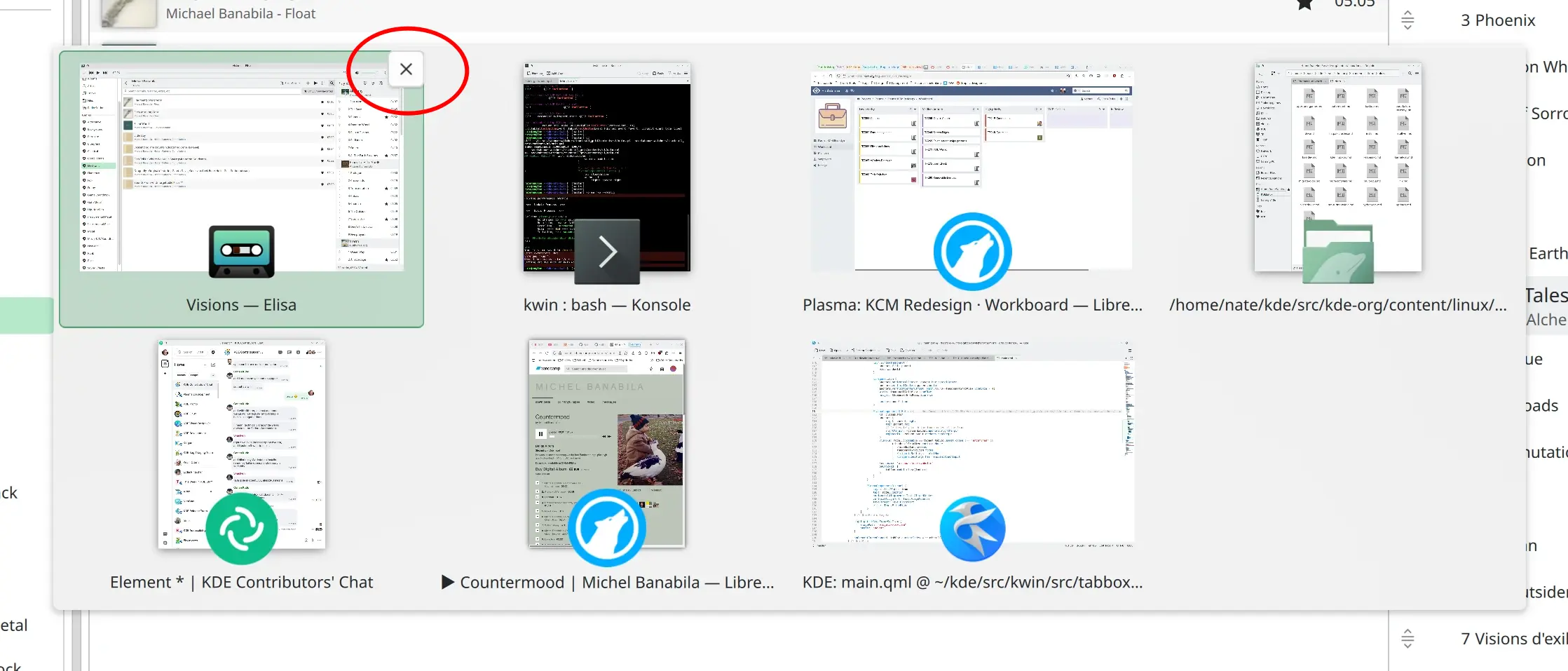

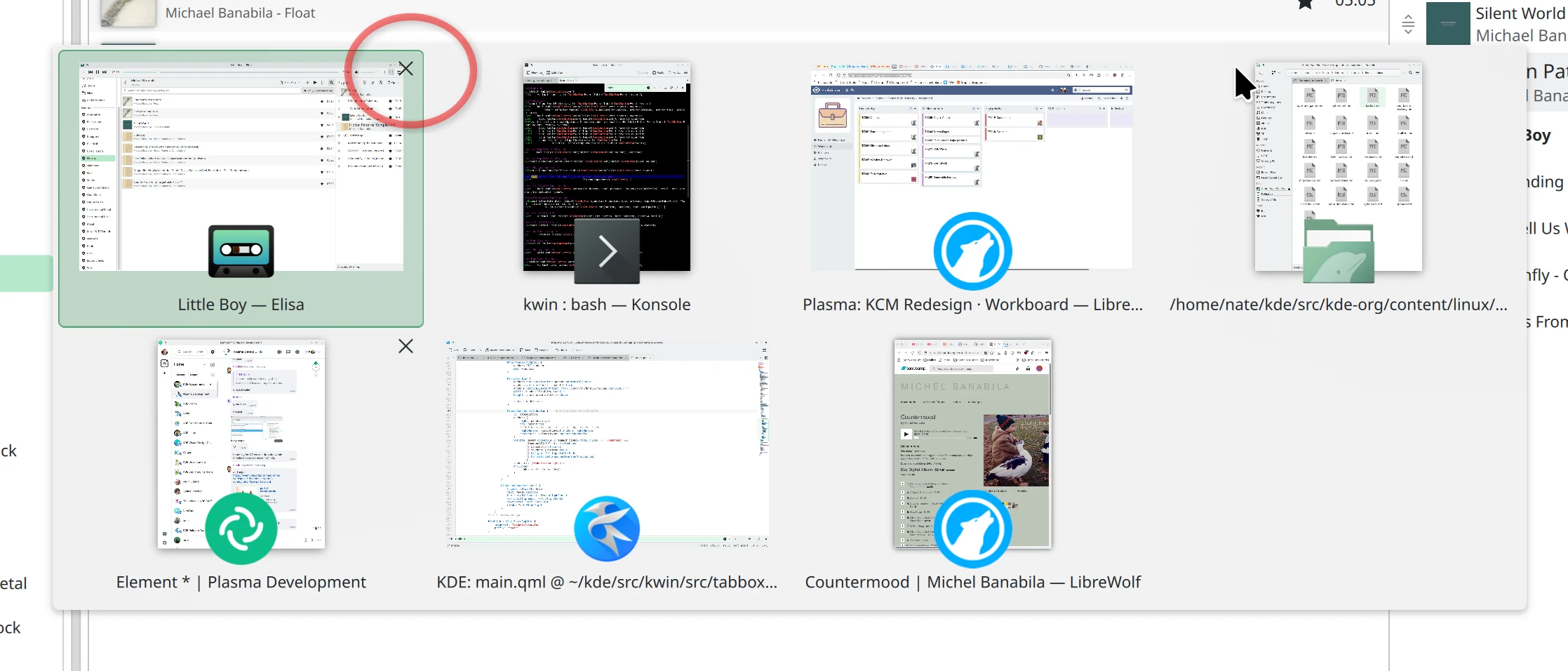

Close buttons on the default “Thumbnails” Alt+Tab task switcher are now more legible on top of the window thumbnails. (Nate Graham, kwin MR #8830)

The Networks widget now shows a more appropriate icon in the panel or System Tray when you disable Wi-Fi. (Nate Graham, plasma-nm MR #526)

Plasma 6.7.0

The System Monitor app and widgets now respect your chosen “binary unit” choice. This means for example if you’ve asked for file sizes to be expressed as “GB” (gigabyte, or one billion bytes) rather than “GiB” (gibibyte, or 2^30 bytes), the system monitoring tools now respect that. (David Redondo, KDE Bugzilla #453854)

If the auto-generated scale factor for a screen is very close to 100%, 200%, or 300%, it now gets rounded to that value, prioritizing performance and visual fidelity. (Kai Uwe Broulik, kwin MR #8742)

The Color Picker widget now displays more sensible tooltip and placeholder text when it hasn’t been used yet. (Joshua Goins, kdeplasma-addons MR #1010)

Various parts of Plasma now consistently use the term “UEFI Firmware Settings” to refer to UEFI-based setup tools. (Kai Uwe Broulik, plasma-workspace MR #6246 and plasma-desktop MR #3541)

The “Terminate this frozen window” dialog now shows a little spinner as it tries to terminate the window, so you don’t think it’s gotten stuck. (Kai Uwe Broulik, kwin MR #8818)

The Widget Explorer sidebar now appears on the screen with the pointer on it, rather than always appearing on the left-most screen. (Fushan Wen, plasma-workspace MR #6251)

Notable bug fixes

Plasma 6.6.1

Fixed a case where KWin could crash during intensive input method usage. (Vlad Zahorodnii, KDE Bugzilla #506916)

Fixed a case where KWin could crash when waking up the system while using the Input Leap or Deskflow input-sharing apps. (David Redondo, KDE Bugzilla #515179)

Fixed a case where Discover could crash while trying to install updates. (Harald Sitter, KDE Bugzilla #515150)

Fixed a regression that broke drag-and-drop onto pinned Task Manager widget icons. (Kai Uwe Broulik, KDE Bugzilla #516242)

Fixed a regression that made certain popups from third-party software appear in the wrong place on the screen. (Vlad Zahorodnii, KDE Bugzilla #516185)

Fixed a minor visual regression in the Zoom effect on rotated screens. (Vlad Zahorodnii, kwin MR #8817)

Fixed a layout regression that made the Task Manager widget’s tooltip close buttons get slightly cut off for multi-window apps while window thumbnails were manually disabled. (Christoph Wolk, KDE Bugzilla #516018)

Fixed a layout regression that slightly misaligned the search bar in the Kicker Application Menu widget. (Christoph Wolk, KDE Bugzilla #516196)

Fixed a layout regression that made some System Tray popups always show an unnecessary hamburger menu. (Arjen Hiemstra, KDE Bugzilla #516135)

Fixed a regression that made some GTK apps not notice system-wide changes to the color scheme and enter their dark mode. (Nicolas Fella, KDE Bugzilla #516303)

Fixed a button added to Plasma 6.6 not having translated text. (Albers Astals Cid, plasma-workspace MR #6305)

Fixed server-to-client clipboard syncing in Plasma’s remote desktop implementation. (realies, krdp MR #144)

The new Plasma Login Manager introduced in Plasma 6.6 no longer shows accounts on the system that a human can’t actually log into. (Matthew Snow, plasma-login-manager MR #109)

Fixed a layout issue that made a label in the panel configuration dialog disappear when using certain Plasma styles. (Filip Fila, KDE Bugzilla #515987)

Fixed a layout issue that made the notification dialog too tall for very short text-only notification messages. (Kai Uwe Broulik, plasma-workspace MR #6145)

Fixed an issue that set the screen brightness to too low a level on login in certain circumstances. (Xaver Hugl, KDE Bugzilla #504441)

Fixed a layout issue that made the song or artist names in the Media Player widget get cut off too early when the widget was placed in a panel in between two spacers. (Greeniac Green, KDE Bugzilla #501166)

Improved the Weather Report widget’s reliability with forecasts from the Environment Canada provider. (Eric Soltys, kdeplasma-addons MR #1008)

Made the progress indicator built into icons in the Task Manager widget move in the appropriate direction when using the system with a right-to-left language like Arabic or Hebrew. (Oliver Beard, KDE Bugzilla #516053)

Custom icons embedded in third-party widgets that appear in the Widget Explorer sidebar now also appear in those widgets’ “About this widget” pages. (Mark Capella, KDE Bugzilla #509896)

Plasma 6.7.0

Eliminated a source of visual glitchiness with certain fade transitions while using an ICC profile. (Xaver Hugl, KDE Bugzilla #515194)

Frameworks 6.24

Fixed a case where KDE’s desktop portal could crash when copying certain data over a remote desktop connection. (David Edmundson, KDE Bugzilla #515465)

Notable in performance & technical

Plasma 6.6.1

Improved animation performance throughout the system by leaning more heavily on the Wayland Presentation Time protocol. (Vlad Zahorodnii, KDE Bugzilla #516240)

How you can help

KDE has become important in the world, and your time and contributions have helped us get there. As we grow, we need your support to keep KDE sustainable.

Would you like to help put together this weekly report? Introduce yourself in the Matrix room and join the team!

Beyond that, you can help KDE by directly getting involved in any other projects. Donating time is actually more impactful than donating money. Each contributor makes a huge difference in KDE — you are not a number or a cog in a machine! You don’t have to be a programmer, either; many other opportunities exist.

You can also help out by making a donation! This helps cover operational costs, salaries, travel expenses for contributors, and in general just keeps KDE bringing Free Software to the world.

To get a new Plasma feature or a bugfix mentioned here

Push a commit to the relevant merge request on invent.kde.org.

Friday, 20 February 2026

Let’s go for my web review for the week 2026-08.

I love the work of the ArchWiki maintainers

Tags: tech, linux, documentation

This is indeed an excellent technical documentation wiki for the Linux ecosystem.

https://k7r.eu/i-love-the-work-of-the-archwiki-maintainers/

Four Lessons From Civic Tech

Tags: tech, politics, commons, business

Interesting lessons indeed. Especially the first one: “Technology is inherently political, and anyone telling you otherwise is trying to hide their politics.” As tech people we too often forget this is all “sociotechnical”, no tech is designed and used in a vacuum.

Hold on to Your Hardware

Tags: tech, hardware, ai, machine-learning, gpt, economics

Are we on the verge to a push toward a mainframe based future? I really hope not, but for sure the hardware prices surging won’t make things easy.

https://xn–gckvb8fzb.com/hold-on-to-your-hardware/

The case for gatekeeping, or: why medieval guilds had it figured out

Tags: tech, foss, community, craftsmanship, ai, copilot, slop

Kind of resonate oddly with the string of talks I gave talking about craftsmanship a decade ago. Looks like FOSS communities at large have no choice but get inspired by such old practice.

https://www.joanwestenberg.com/the-case-for-gatekeeping-or-why-medieval-guilds-had-it-figured-out/

Open-source game engine Godot is drowning in ‘AI slop’ code contributions

Tags: tech, ai, machine-learning, copilot, slop, github

Another example of how much of a problem this is for some projects. Of course it is compounded by having so many projects on GitHub, this pushes people to try to farm for activity to attempt to make their resume look good. This is sad.

What Your Bluetooth Devices Reveal About You

Tags: tech, bluetooth, security, privacy

Bluetooth might be convenient, clearly it leads to metadata leakage though.

https://blog.dmcc.io/journal/2026-bluetooth-privacy-bluehood/

Obfuscate data by hiding it in images

Tags: tech, security, cryptography, colors, graphics

I’ve always been fascinated by steganography. It’s a good reminder that the basics are fairly simple.

Self-hosting my websites using bootable containers

Tags: tech, linux, bootc, system, systemd, self-hosting

Interesting setup for self hosting on immutable infrastructure using bootc.

https://yorickpeterse.com/articles/self-hosting-my-websites-using-bootable-containers/

TIL: Docker log rotation

Tags: tech, docker, logging

I find surprising it’s not by default… But here we are.

https://ntietz.com/blog/til-docker-log-rotation/

Compendium

Tags: tech, system, observability, strace, linux

Still very young but it looks like it might become a nice and friendly alternative to strace.

https://pker.xyz/posts/compendium

Linux terminal emulator architecture

Tags: tech, linux, terminal, system

A good one page primer on how terminal emulators are designed.

Runtime validation in type annotations

Tags: tech, python, type-systems

Interesting new tricks with the introspection of Python type annotations.

https://blog.natfu.be/validation-in-type-annotations/

How bad can Python stop-the-world pauses get?

Tags: tech, python, memory, performance

Of course it’s a question of the amount of allocations you need.

https://lemire.me/blog/2026/02/15/how-bad-can-python-stop-the-world-pauses-get/

C++26: std::is_within_lifetime

Tags: tech, c++, type-systems

A small change in the standard, but it opens the door to interesting uses.

https://www.sandordargo.com/blog/2026/02/18/cpp26-std_is_within_lifetime

spix: UI test automation library for QtQuick/QML Apps

Tags: tech, qt, tests, gui

Still young but looks like a nice option to write GUI tests for Qt based applications.

https://github.com/faaxm/spix?tab=readme-ov-file

Fast sorting, branchless by design

Tags: tech, algorithm, security

Didn’t know about sorting networks. They have interesting properties and are definitely good options on modern hardware.

https://00f.net/2026/02/17/sorting-without-leaking-secrets/

How Michael Abrash doubled Quake framerate

Tags: tech, game, optimisation, assembly, graphics

Interesting insights from optimisations done on the Quake engine almost thirty years ago.

https://fabiensanglard.net/quake_asm_optimizations/index.html

Font Rendering from First Principles

Tags: tech, fonts, graphics

We take font rendering for granted but this is more complex than one might think.

https://mccloskeybr.com/articles/font_rendering.html

Modern CSS Code Snippets

Tags: tech, web, frontend, css

Another nice resource to discover newer CSS idioms.

Stop Guessing Worker Counts

Tags: tech, distributed, messaging, performance

We got some math for that! No need to guess.

The 12-Factor App - 15 Years later. Does it Still Hold Up in 2026?

Tags: tech, services, infrastructure, cloud, devops

A bit buzzword oriented, still I think it’s true that most of those principles make sense.

The only developer productivity metrics that matter

Tags: tech, agile, productivity, metrics

I agree with this very much. The only productivity metric in the end is the end-user satisfaction.

https://genehack.blog/2026/02/the-only-developer-productivity-metrics-that-matter/

You can code only 4 hours per day. Here’s why.

Tags: tech, engineering, cognition, organisation, communication, productivity

Quite some good tips in there. If you want to do deep work you need to arrange your organisation for it. Using asynchronous communication more is also key in my opinion.

https://newsletter.techworld-with-milan.com/p/you-can-code-only-4-hours-per-day

Poor Deming never stood a chance

Tags: management, leadership

Interesting comparison of Drucker’s and Deming’s approaches to management. One is easier while the other is clearly demanding but brings lasting improvements.

https://surfingcomplexity.blog/2026/02/16/poor-deming-never-stood-a-chance/

In a blind test, audiophiles couldn’t tell the difference between audio signals sent through copper wire, a banana, or wet mud

Tags: audio, music, physics, funny

Can we stop with the audiophile snobbery now?

Bye for now!

Today we're releasing the second beta of Krita 5.3.0 and Krita 6.0.0. Our thanks to all the people who have tested the first beta. We received 49 bug reports in total, of which we managed to resolve 14 for this release.

Note that 6.0.0-beta2 has more issues, especially on Linux and Wayland, than 5.3.0-beta2. If you want to combine beta testing with actual productive work, it's best to test 5.3.0-beta2, since 5.3.0 will remain the recommended version of Krita for now.

This release also has the new splash screen by Tyson Tan - "Kiki Paints Over the Waves"!

To learn about everything that has changed, check the release notes!

5.3.0-beta2 Download

Windows

If you're using the portable zip files, just open the zip file in Explorer and drag the folder somewhere convenient, then double-click on the Krita icon in the folder. This will not impact an installed version of Krita, though it will share your settings and custom resources with your regular installed version of Krita. For reporting crashes, also get the debug symbols folder.

[!NOTE] We are no longer making 32-bit Windows builds.

64 bits Windows Installer: krita-x64-5.3.0-beta2-setup.exe

Portable 64 bits Windows: krita-x64-5.3.0-beta2.zip

Linux

Note: starting with recent releases, the minimum supported distro versions may change.

[!WARNING] Starting with recent AppImage runtime updates, some AppImageLauncher versions may be incompatible. See AppImage runtime docs for troubleshooting.

- 64 bits Linux: krita-5.3.0-beta2-x86_64.AppImage

MacOS

Note: minimum supported MacOS may change between releases.

- MacOS disk image: krita-5.3.0-beta2-signed.dmg

Android

Krita on Android is still beta; tablets only.

Source code

You can build Krita 5.3 using the Krita 6.0.0.source archives. The difference is which version of Qt you build against.

md5sum

For all downloads, visit https://download.kde.org/unstable/krita/5.3.0-beta2/ and click on "Details" to get the hashes.

6.0.0-beta2 Download

Windows

If you're using the portable zip files, just open the zip file in Explorer and drag the folder somewhere convenient, then double-click on the Krita icon in the folder. This will not impact an installed version of Krita, though it will share your settings and custom resources with your regular installed version of Krita. For reporting crashes, also get the debug symbols folder.

[!NOTE] We are no longer making 32-bit Windows builds.

64 bits Windows Installer: krita-x64-6.0.0-beta2-setup.exe

Portable 64 bits Windows: krita-x64-6.0.0-beta2.zip

Linux

Note: starting with recent releases, the minimum supported distro versions may change.

[!WARNING] Starting with recent AppImage runtime updates, some AppImageLauncher versions may be incompatible. See AppImage runtime docs for troubleshooting.

- 64 bits Linux: krita-6.0.0-beta2-x86_64.AppImage

MacOS

Note: minimum supported MacOS may change between releases.

- MacOS disk image: krita-6.0.0-beta2-signed.dmg

Android

Due to issues with Qt6 and Android, we cannot make APK builds for Android of Krita 6.0.0-beta2.

Source code

md5sum

For all downloads, visit https://download.kde.org/unstable/krita/6.0.0-beta2/ and click on "Details" to get the hashes.

Key

The Linux AppImage and the source tarballs are signed. You can retrieve the public key here. The signatures are here (filenames ending in .sig).

Thursday, 19 February 2026

Automating Repetitive GUI Interactions in Embedded Development with Spix

As Embedded Software Developers, we all know the pain: you make a code change, rebuild your project, restart the application - and then spend precious seconds repeating the same five clicks just to reach the screen you want to test. Add a login dialog on top of it, and suddenly those seconds turn into minutes. Multiply that by a hundred iterations per day, and it’s clear: this workflow is frustrating, error-prone, and a waste of valuable development time.

In this article, we’ll look at how to automate these repetitive steps using Spix, an open-source tool for GUI automation in Qt/QML applications. We’ll cover setup, usage scenarios, and how Spix can be integrated into your workflow to save hours of clicking, typing, and waiting.

The Problem: Click Fatigue in GUI Testing

Imagine this:

- You start your application.

- The login screen appears.

- You enter your username and password.

- You click "Login".

- Only then do you finally reach the UI where you can verify whether your code changes worked.

This is fine the first few times - but if you’re doing it 100+ times a day, it becomes a serious bottleneck. While features like hot reload can help in some cases, they aren’t always applicable - especially when structural changes are involved or when you must work with "real" production data.

So, what’s the alternative?

The Solution: Automating GUI Input with Spix

Spix allows you to control your Qt/QML applications programmatically. Using scripts (typically Python), you can automatically:

- Insert text into input fields

- Click buttons

- Wait for UI elements to appear

- Take and compare screenshots

This means you can automate login steps, set up UI states consistently, and even extend your CI pipeline with visual testing. Unlike manual hot reload tweaks or hardcoding start screens, Spix provides an external, scriptable solution without altering your application logic.

Setting up Spix in Your Project

Getting Spix integrated requires a few straightforward steps:

1. Add Spix as a dependency

- Typically done via a Git submodule into your project’s third-party folder.

git submodule add 3rdparty/spix git@github.com:faaxm/spix.git2. Register Spix in CMake

- Update your

CMakeLists.txtwith afind_package(Spix REQUIRED)call. - Because of CMake quirks, you may also need to manually specify the path to Spix’s CMake modules.

LIST(APPEND CMAKE_MODULE_PATH /home/christoph/KDAB/spix/cmake/modules)

find_package(Spix REQUIRED)3. Link against Spix

- Add

Spixto yourtarget_link_librariescall.

target_link_libraries(myApp

PRIVATE Qt6::Core

Qt6::Quick

Qt6::SerialPort

Spix::Spix

)4. Initialize Spix in your application

- Include Spix headers in

main.cpp. - Add some lines of boilerplate code:

- Include the 2 Spix Headers (AnyRPCServer for Communication and QtQmlBot)

- Start the Spix RPC server.

- Create a

Spix::QtQmlBot. - Run the test server on a specified port (e.g.

9000).

#include <Spix/AnyRpcServer.h>

#include <Spix/QtQmlBot.h>

[...]

//Start the actual Runner/Server

spix::AnyRpcServer server;

auto bot = new spix::QtQmlBot();

bot->runTestServer(server);At this point, your application is "Spix-enabled". You can verify this by checking for the open port (e.g. localhost:9000).

Spix can be a Security Risk: Make sure to not expose Spix in any production environment, maybe only enable it for your Debug-builds.

Where Spix Shines

Once the setup is done, Spix can be used to automate repetitive tasks. Let’s look at two particularly useful examples:

1. Automating Logins with a Python Script

Instead of typing your credentials and clicking "Login" manually, you can write a simple Python script that:

- Connects to the Spix server on

localhost:9000 - Inputs text into the

userFieldandpasswordField - Clicks the "Login" button (Items marked with "Quotes" are literal That-Specific-Text-Identifiers for Spix)

import xmlrpc.client

session = xmlrpc.client.ServerProxy('http://localhost:9000')

session.inputText('mainWindow/userField', 'christoph')

session.inputText('mainWindow/passwordField', 'secret')

session.mouseClick('mainWindow/"Login"')When executed, this script takes care of the entire login flow - no typing, no clicking, no wasted time. Better yet, you can check the script into your repository, so your whole team can reuse it.

For Development, Integration in Qt-Creator can be achieved with a Custom startup executable, that also starts this python script.

In a CI environment, this approach is particularly powerful, since you can ensure every test run starts from a clean state without relying on manual navigation.

2. Screenshot Comparison

Beyond input automation, Spix also supports taking screenshots. Combined with Python libraries like OpenCV or scikit-image, this opens up interesting possibilities for testing.

Example 1: Full-screen comparison

Take a screenshot of the main window and store it first:

import xmlrpc.client

session = xmlrpc.client.ServerProxy('http://localhost:9000')

[...]

session.takeScreenshot('mainWindow', '/tmp/screenshot.png')kNow we can compare it with a reference image:

from skimage import io

from skimage.metrics import structural_similarity as ssim

screenshot1 = io.imread('/tmp/reference.png', as_gray=True)

screenshot2 = io.imread('/tmp/screenshot.png', as_gray=True)

ssim_index = ssim(screenshot1, screenshot2, data_range=screenshot1.max() - screenshot1.min())

threshold = 0.95

if ssim_index == 1.0:

print("The screenshots are a perfect match")

elif ssim_index >= threshold:

print("The screenshots are similar, similarity: " + str(ssim_index * 100) + "%")

else:

print("The screenshots are not similar at all, similarity: " + str(ssim_index * 100) + "%")This is useful for catching unexpected regressions in visual layout.

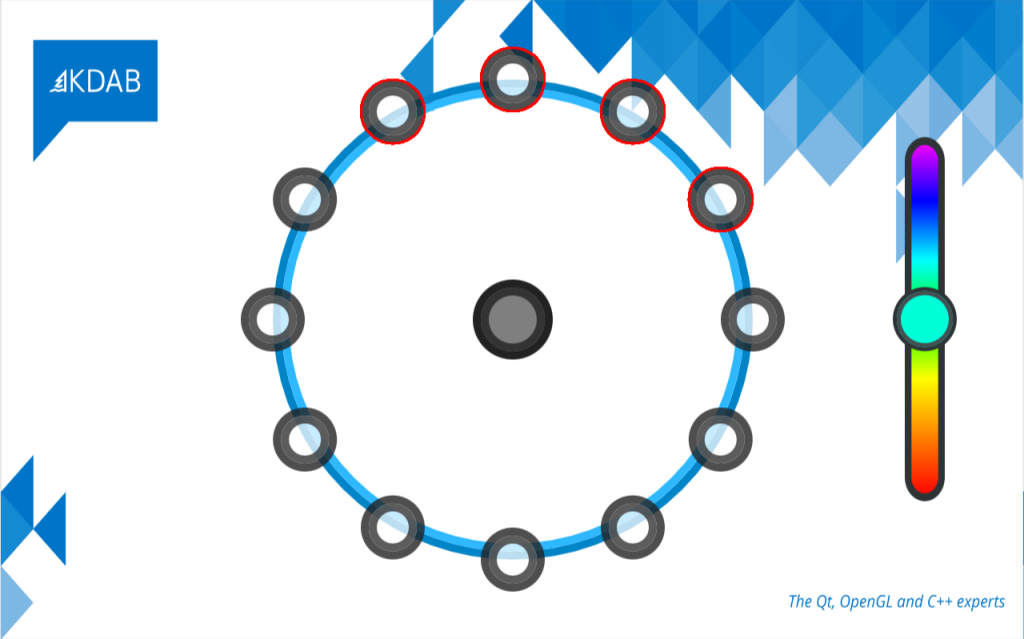

Example 2: Finding differences in the same UI

Use OpenCV to highlight pixel-level differences between two screenshots—for instance, missing or misaligned elements:

import cv2

image1 = cv2.imread('/tmp/reference.png')

image2 = cv2.imread('/tmp/screenshot.png')

diff = cv2.absdiff(image1, image2)

# Convert the difference image to grayscale

gray = cv2.cvtColor(diff, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY)

# Threshold the grayscale image to get a binary image

_, thresh = cv2.threshold(gray, 30, 255, cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

contours, _ = cv2.findContours(thresh, cv2.RETR_EXTERNAL, cv2.CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE)

cv2.drawContours(image1, contours, -1, (0, 0, 255), 2)

cv2.imshow('Difference Image', image1)

cv2.waitKey(0)This form of visual regression testing can be integrated into your CI system. If the UI changes unintentionally, Spix can detect it and trigger an alert.

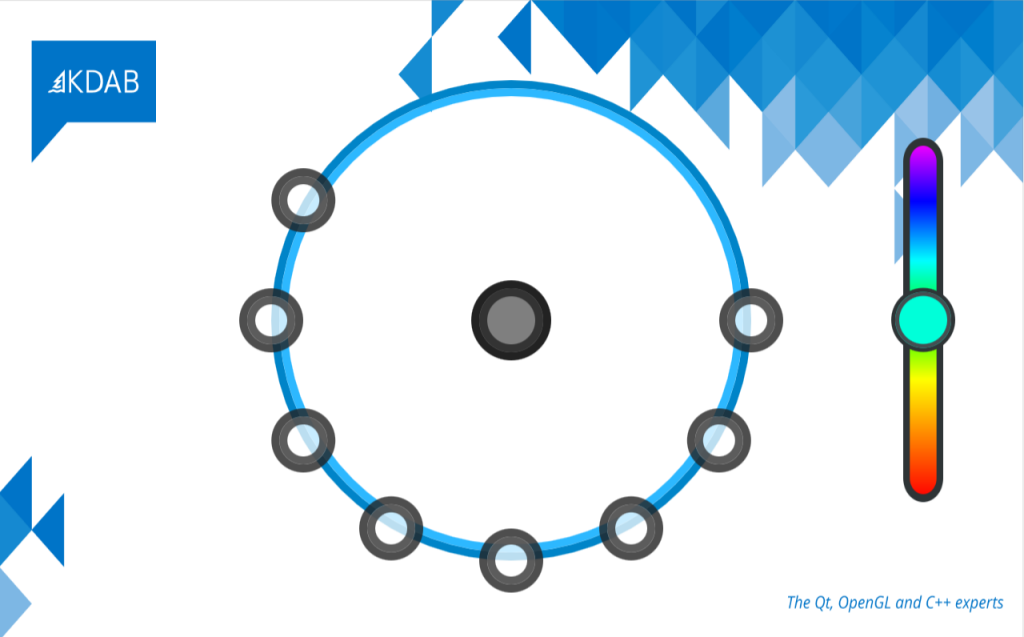

Defective Image

The script marked the defective parts of the image compared to the should-be image.

Recap

Spix is not a full-blown GUI testing framework like Squish, but it fills a useful niche for embedded developers who want to:

- Save time on repetitive input (like logins).

- Share reproducible setup scripts with colleagues.

- Perform lightweight visual regression testing in CI.

- Interact with their applications on embedded devices remotely.

While there are limitations (e.g. manual wait times, lack of deep synchronization with UI states), Spix provides a powerful and flexible way to automate everyday development tasks - without having to alter your application logic.

If you’re tired of clicking the same buttons all day, give Spix a try. It might just save you hours of time and frustration in your embedded development workflow.

The post Automating Repetitive GUI Interactions in Embedded Development with Spix appeared first on KDAB.

toscalix

toscalix

@shibe_13:matrix.org

@shibe_13:matrix.org