Akademy 2025 group photo.

Akademy 2025 group photo.

This year's Akademy took place in Berlin, Germany. The city's modernity and avant-garde counterculture atmosphere fit very well with the current mood in the KDE community. As volunteer developers push forward with technologies that even multi-billion dollar corporations struggle to imitate, there is a general feeling that something great is on the horizon. With major migrations and potential adoptions in public administrations, not to mention KDE technologies making their way into all kinds of devices, it seems that we are finally on the verge of going mainstream and bringing FLOSS to the general public.

Bearing all this in mind, the community gathered at Berlin's Technische Universität for an intense week of KDE-related activities.

Saturday, 6 September 2025

On Saturday morning, and as is traditional, Aleix Pol, President of KDE e.V., kicked proceedings off at 9:30 sharp. Aleix told us about what we should expect, reminded us about accreditations and lanyards. He also told us about the where the talks, BoFs, coffee breaks and sponsor booths were for when we needed a break.

Aleix Pol officially opens Akademy.

Aleix Pol officially opens Akademy.

And with that we were off!

In our first keynote, Alexander Rosenthal, project leader at DigitalHub.SH in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, explained the exciting migration to Free Software going on in the region.

The focus was mainly on digital sovereignty and how public administrations should look to FLOSS to recover ownership of their infrastructures, devices and data, but the bit that drew the loudest applause was when Alexander mentioned that Plasma was the front-runner to power the institutional desktops in the region.

Alexander Rosenthal tells attendees about what is going with Schleswig-Holstein's migration to Free Software.

Alexander Rosenthal tells attendees about what is going with Schleswig-Holstein's migration to Free Software.

After the coffee break, David Edmundson talked about Plasma's reputation, how several mistakes had marked it for a long time, how we have overcome the bad press and what we can do to move forward and avoid the same pitfalls again.

In room 2, Karanjot Singh told us about KEcoLab, an automation tool for energy consumption measurements that allows KDE developers to remotely measure the energy consumption of their KDE software through GitLab CI/CD.

This means that Instead of obtaining measurements manually and in person in a lab such as the one at KDAB, Berlin, KDE developers can trigger the process through CI/CD, wherever they are. This enables developers to effortlessly assess their software's energy consumption when merging new code into the codebase.

After that, and back in room 1, Andy Betts presented the latest in the design goals presented for the first time at last year's Akademy. Andy provided a list of all the updates and implementations including a review on variable availability for designers and developers.

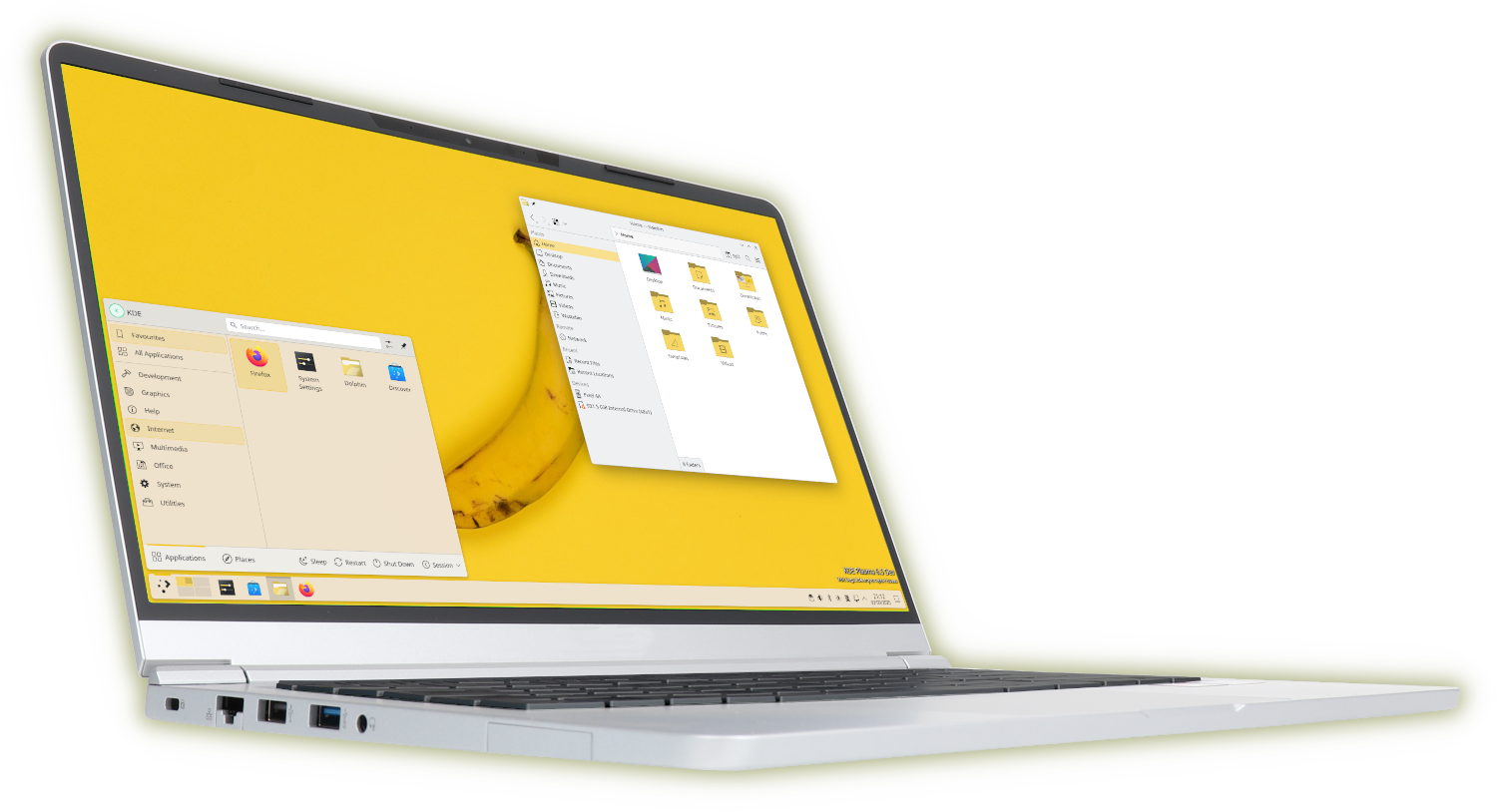

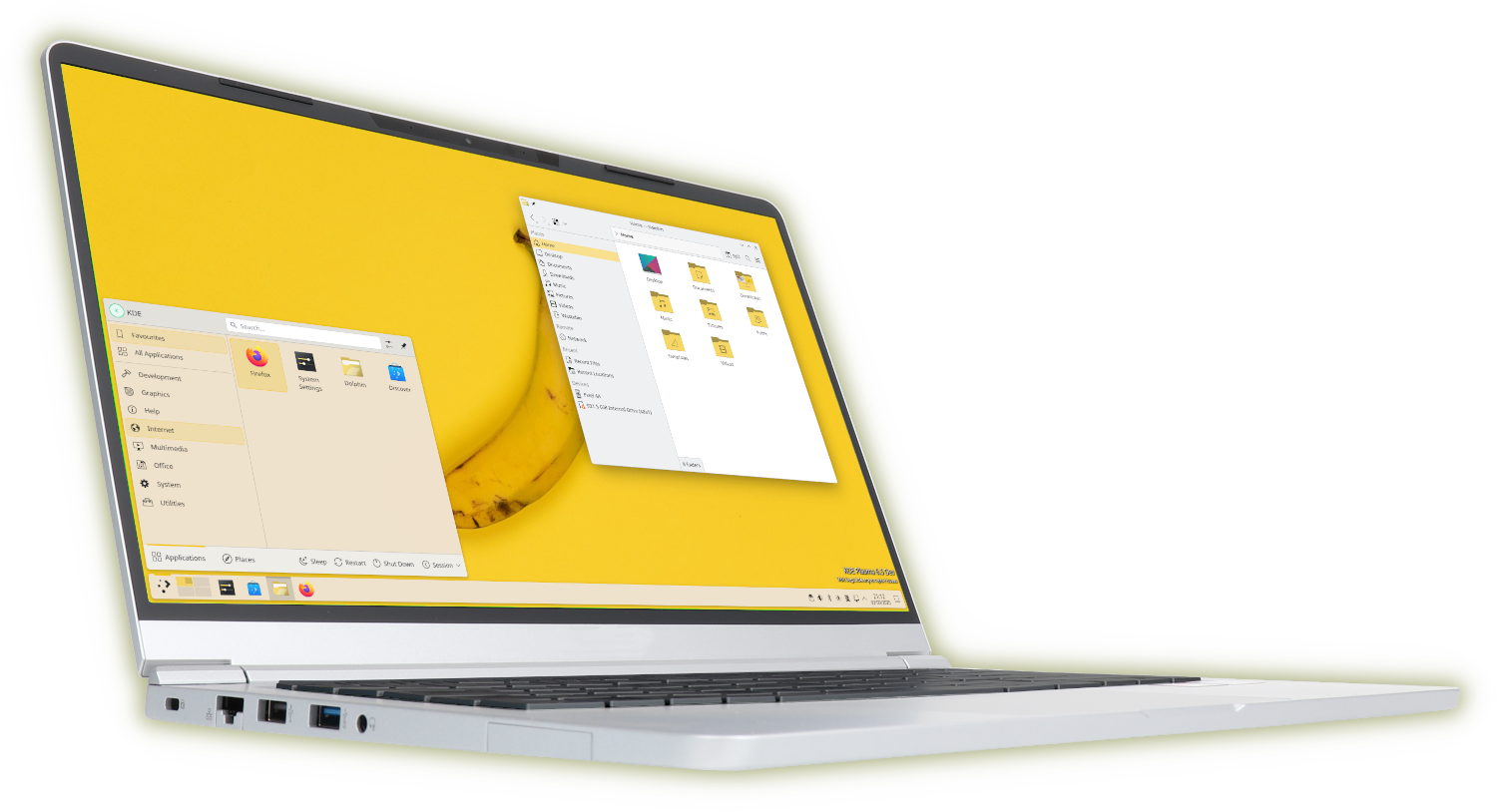

Artist's impression of KDE Linux.

Artist's impression of KDE Linux.

Meanwhile, in room 2, everyone was excitedly listening to Harald Sitter release the first alpha version of KDE Linux. Based on an idea launched back during Akademy 2024, KDE's reference distro for KDE technologies is now in a good enough state for it to be easily tested.

Harald Sitter mit Bananen.

Harald Sitter mit Bananen.

A little after 2 pm, Bettina Louis, Carolina Silva Rode, Joseph De Veaugh-Geiss, and Nicole Teale took to the stage in room 1 to tell us about how the End of 10 campaign is going. The answer was "very well". Designed by the KDE Eco team to try and curb the environmental disaster that Microsoft's end of support for Windows 10 will entail, the campaign encourages users not to ditch their older machines that do not support Windows 11, and do a real upgrade and install Linux instead.

The campaign caught the FLOSS community's imagination and has sparked installfests, inspired news stories, and revitalised repair cafés all over the world.

At the same time in room 2, Cristián Maureira-Fredes from The Qt Company told us about how bindings to newer languages, like Qt for Python have been around to open the doors to new generations of developers, and how one of the Qt's goals was to find ways of unlocking their framework’s features for even more programming languages without the need to rely on bindings or learning C++.

At 15:35 we had the traditional Report of the Board in room 1. KDE e.V. board members Adriaan De Groot, Aleix Pol González, Eike Hein, Lydia Pintscher and Nate Graham talked about the work of the organization over the past year and what is coming next.

This session was followed by the annual report of the Working Groups, led by Lydia Pintscher. The Working Groups help the KDE Community in various areas such as fundraising, community management and running our infrastructure.

The third session in this vein was the KDE Goals - One year recap. Farid Abdelnour, Nicolas Fella, Jakob Petsovits, Gernot Schiller and Paul Brown talked about how the KDE goals that were set at Akademy 2024 were going one year on.

Meanwhile, in room 2, Arjen Hiemstra was discussing buttons, sidebars and other graphical elements and how they get rendered in KDE applications during his talk on the Union styling system. Arjen introduced Union at Akademy 2024 and the project aims to create a styling engine that unifies the various styling methods used in KDE. Arjen covered the progress made to achieve this goal and some of the new major features that have been developed, the state of adopting Union within KDE and some plans for the future.

Arjen was followed by Kevin Ottens, who talked about the progress made in the "KDE Neon Core" project, and effort to bring Plasma to Ubuntu Core.

And then Alexandra Betouni took to the stage and talked of her real-life experience trying to claim a space in the male-dominated tech industry.

At 18:00, Nicolas Fella was looking at KDE Frameworks' bindings to other languages (apart from C++), such as Python and Rust. Nicolas explained why this was important, how the binding generation worked under the hood and how they can be used in applications

In room 1, lightning talks, talks that last between 5 and 10 minutes, were kicking off, opening with Emilia Valkonen-Damjanovic, who introduced attendees to Qt Academy and the future plans for an official Qt developer certifications.

She was followed by Marco Martin, who tackled the controversial idea of retiring KWallet, a venerable app that needs to be superseded by a more modern approach to password safety.

Then Volker Krause talked about how to implement emergency and weather alerts into free software systems. Interestingly Volker's implementation in kpublicalerts was put to the test during the BoF when the citizens of Berlin received an alert regarding bad weather. Ultimately, the emergency alert system will be built into Plasma/Plasma Mobile itself, as it should not have to rely on an external app.

Finally Alexander Lohnau gave us an overview of Clazy, KDE's static code analyzer for Qt and C++, and how it can boost developers' workflow, helping them write cleaner, faster, and more reliable code.

Sunday, 7 September 2025

The first session on Sunday started at 10:00 and featured Paloma Oliveira from the Sovereign Tech Agency who spoke about how KDE could become more diverse, not by implementing rigid rules, but with “gentle enforcement”, by establishing communication patterns, governance models, and accountability mechanisms that help communities grow in more just and inclusive directions.

Paloma Oliveira explains how soft power is effective to encourage a shift towards diversification and inclusivity.

Paloma Oliveira explains how soft power is effective to encourage a shift towards diversification and inclusivity.

After a quick break, we were back in room 1 with Akseli Lahtinen, who spoke from the heart of his experience on how he had been badmouthed, harassed and received hate mail just for implementing features or trying to improve KDE's UIs, and how he had handled it.

In room 2, Sune Stolborg Vuorela told us about CppCheck, a static code analyzer that can be integrated into KDE's CI workflow on invent, and how to get properly started with it.

After lunch, Akademy participants posed for the Akademy 2025 group photo and then went on to listen to David Edmundson, who explained that, while attracting contributors to project is relatively simple, recruiting maintainers is less so. He then gave advice on how to do just that.

David Edmundson talks about how to recruit project maintainers.

David Edmundson talks about how to recruit project maintainers.

At the same time, Aleix Pol was in room 2 talking about Flatpak and dished out advice on how to make Flatpak an actual environment where applications are developed.

Later, in room 1, Till Adam, of KDAB, tackled the thorny subject of FLOSS and business. Drawing from his own experience, Till expounded on the dos and don'ts of growing an enterprise from community roots.

Another interesting business-related talk by Patrick Fitzgerald followed. Patrick explained strategies for massive migrations from Windows to Linux, the potential pitfalls migrators face, and how to come out on top in the end.

In room 2, Ulf Hermann covered the new technologies coming to Qt 6.10 that allow developers to expose data to QML.

This was followed up by Nicolas Fella, who explained how developers can leverage the new QDoc system to generate better documentation for their projects.

Back in room 1, Nate Graham was telling us how, even though the world is a mess right now, that same chaos opened up opportunities for projects like KDE and how the community could take advantage of them.

In room 2, Neal Gompa presented a brief history of Fedora KDE Plasma Desktop Edition, success story of how community pressed for a distro to become a recognized flagship offering, and what happens next.

Then, artist and developer Joshus Goins looked at the steps taken in Plasma 6 to make KDE's desktop artist friendly, and how things will go from here on onwards.

At 17:15, lightning talks were starting up again in room 1, and Nicolas Fella kicked them off explaining the theory and practice of effective intra-team communication.

David Edmundson followed, continuing with the theme of communication, and told us what makes an effective commit message.

Bhushan Shah was up next with a talk about the state of power management in Plasma Mobile.

And finally, Jean-Baptiste Mardelle told us about Kdenlive's fundraising efforts and plans, where the money goes, and what they intend to fund next.

Then it was turn for the sponsor's talks and representatives from The Qt Group, KDAB, openSUSE, and Enioka Haute Couture took to the stage to tell attendees about their companies and how they are involved in KDE.

Aleix Pol stood in for Canonical, as the rep who was supposed to be at the event was sick and could not make it.

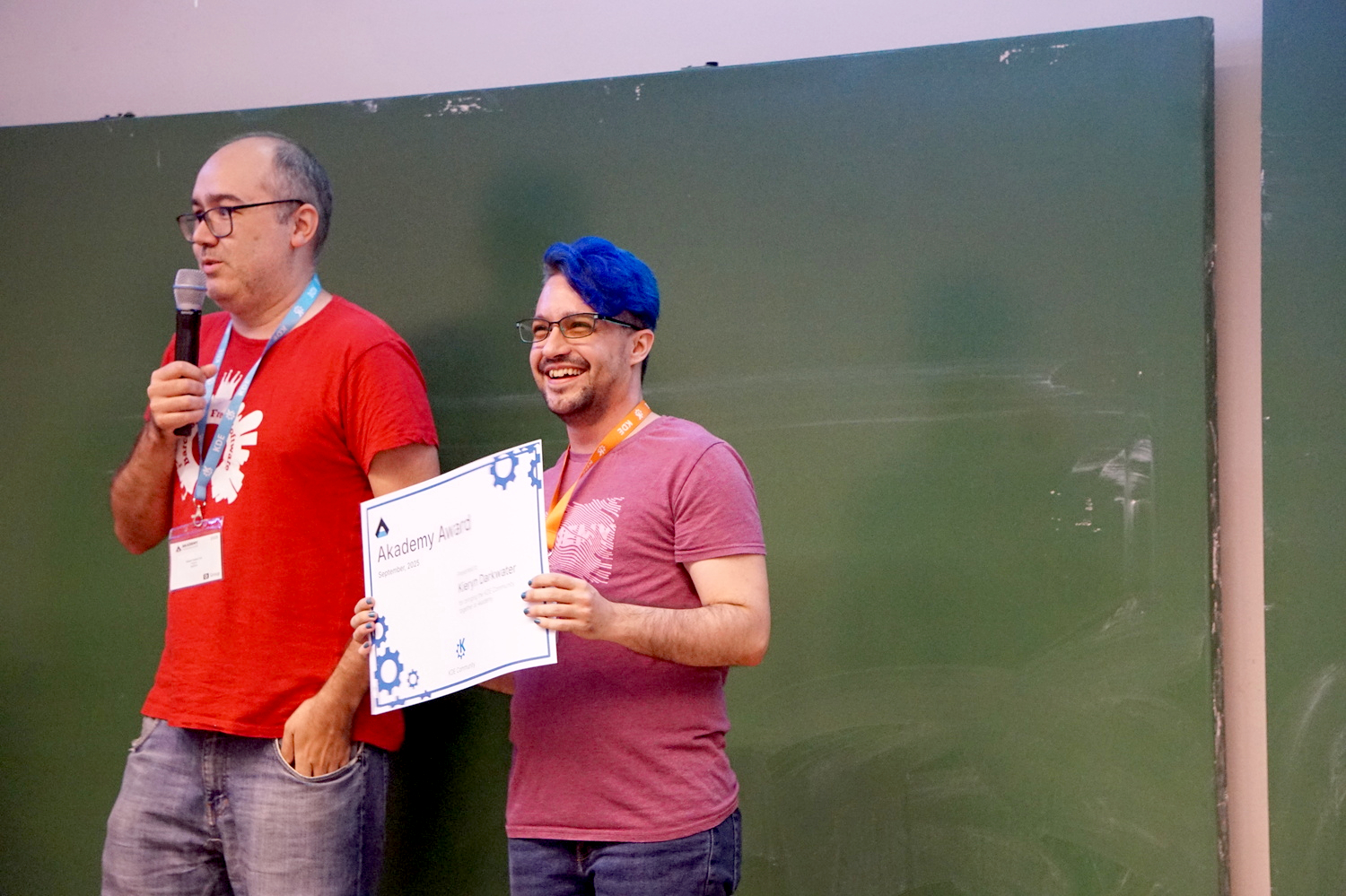

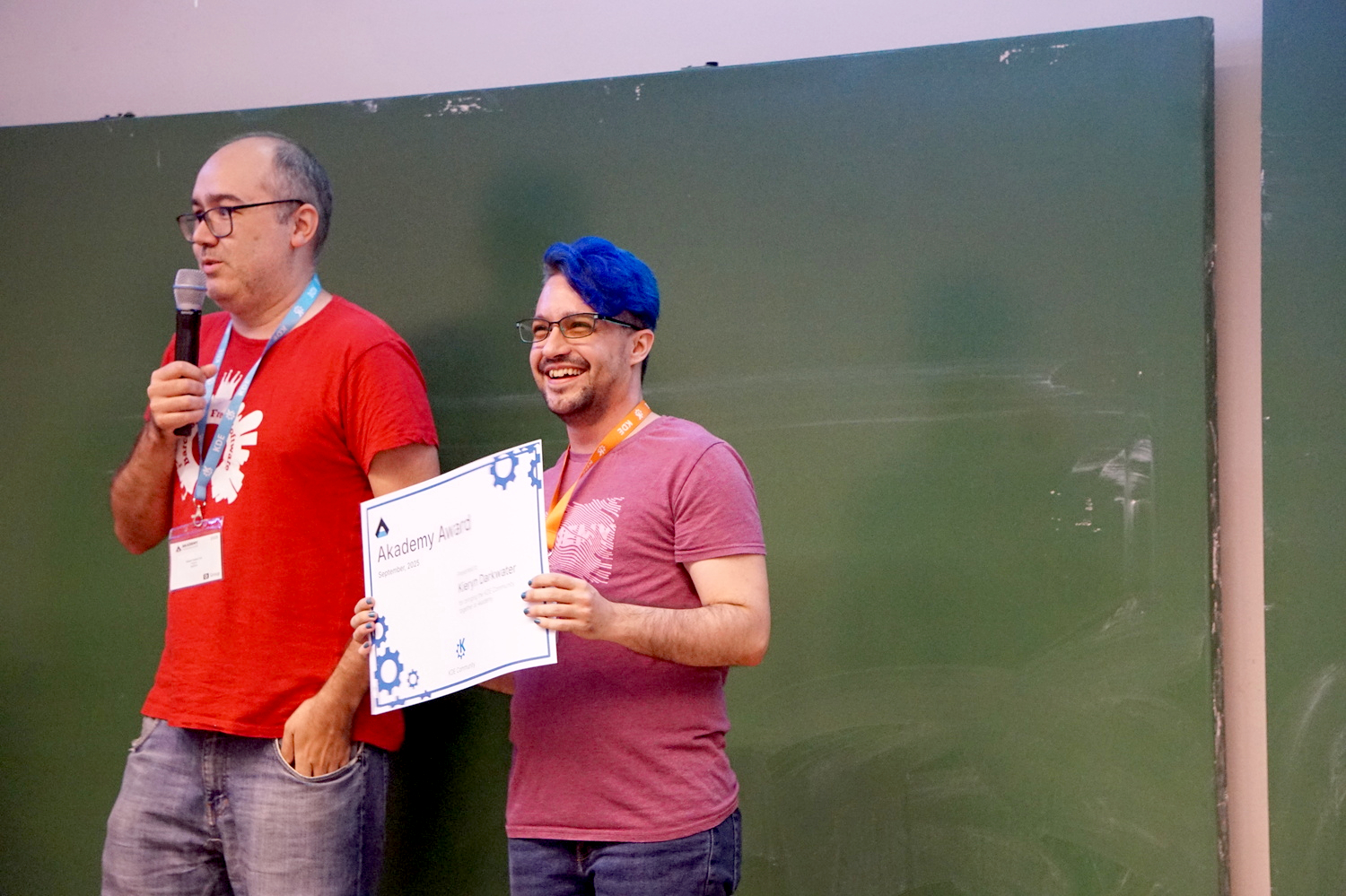

The last on-site of the day was the KDE Award ceremony. Vlad Zahorodnii and Xaver Hugl were awarded for their work on KWin and Wayland. Then Alexander Lohnau received an award for his work on Frameworks, Clazy and Krunner. Allen Winter was presented for an award in absentia for his work on KDE PIM and many years of contributions to other projects.

Finally, Kieryn Darkwater received an award in the name of all the Akademy organisers for organising such a great Akademy.

Albert Astals presents Kieryn Darkwater with an award for organizing an excellent Akademy.

Albert Astals presents Kieryn Darkwater with an award for organizing an excellent Akademy.

For the after-dark track of Akademy, attendees retired to c-base, Berlin's repurposed crashed space station and hackerspace, to discuss, relax and enjoy the community vibe.

@merritt:kde.org

@merritt:kde.org

cullmann

cullmann