Saturday, 14 February 2026

So, while working with caching and scrapping, I understood the difference between immutable and mutable objects/datatypes very clearly. I had a scenario, where I am webscraping an API, the code looks like this.

from aiocache import cached

@cached(ttl=7200)

async def get_forecast(station_id: str) -> list[dict]:

data: dict = await scrape_weather(station_id)

# doing some operation

return forecasts

and then using this utility tool in the endpoint.

async def get_forecast_by_city(

param: Annotated[StationIDQuery, Query()],

) -> list[UpcomingForecast]:

forecasts_dict: list[dict] = await get_forecast(param.station_id)

forecasts_dict.reversed()

forecasts: deque[UpcomingForecast] = deque([])

for forecast in forecasts_dict:

date_delta: int = (

date.fromisoformat(forecast["forecast_date"]) - date.today()

).days

if date_delta <= 0:

break

forecasts.appendleft(UpcomingForecast.model_validate(forecast))

return list(forecasts)

But, here is the gotcha, something I was doing inherently wrong. Lists in python are mutable objects. So, reversing the list modifies the list in place, without creating a new reference of the list. My initial approach was to do this

Welcome to a new issue of This Week in Plasma!

This week we put the finishing touches on Plasma 6.6! It’s due to be released in just a few days and it’s a great release with tons of impactful features, UI improvements, and bug fixes. I hope everyone loves it!

Meanwhile, check out what folks were up to this week:

Notable UI Improvements

Plasma 6.7.0

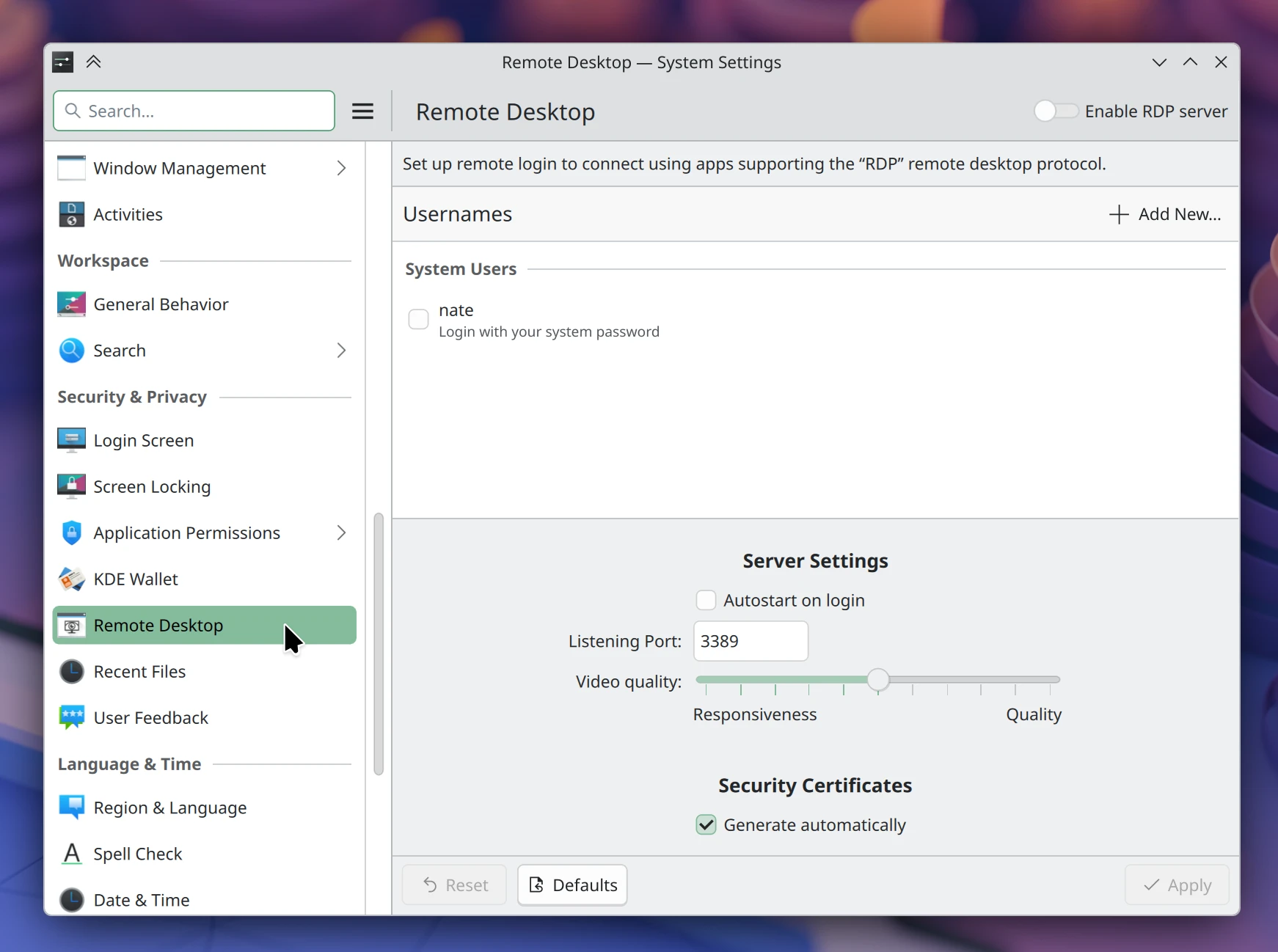

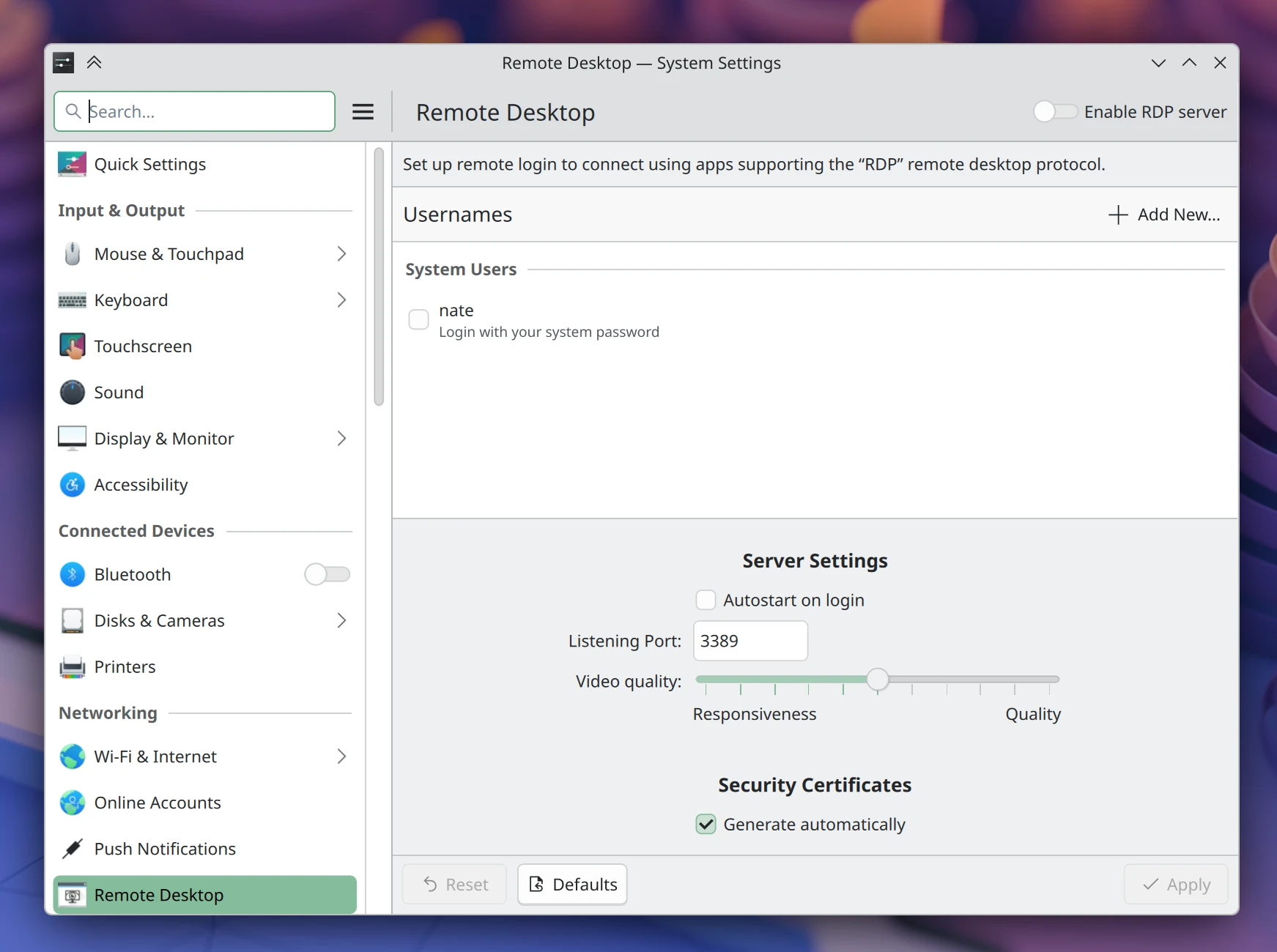

Moved System Settings’ “Remote Desktop” page to the “Security & Privacy” group in System Settings. (Nate Graham, krdp MR #139)

Improved the way loop devices are handled in the Disks & Devices widget. (Bogdan Onofriichuk, plasma-workspace MR #6260)

Reduced visual jagginess in the split image effect of wallpaper previews that show both a light and dark version. (Fushan Wen, plasma-workspace MR #6283)

The Kicker Application Menu widget now supports using a non-square icon for its panel button, just like Kickoff does. (Christoph Wolk, plasma-desktop MR #3522)

Added a dedicated global action for un-tiling a quick-tiled window. It doesn’t have a keyboard shortcut by default, but you can assign one yourself. (Kevin Azzam, KDE Bugzilla #500636)

Videos in SDDM login screen themes can now be previewed in System Settings. (Blue Terracotta, sddm-kcm MR #99)

Improved the appearance of various dialogs created by KWin. Read more here! (Kai Uwe Broulik, kwin MR #8702)

You can now configure how long it takes the window switcher to appear after you start holding down Alt+Tab. (Guilherme Soares, KDE Bugzilla #486389)

Frameworks 6.24

In Kirigami-based apps, hovering the pointer over buttons that can be triggered with keyboard shortcuts now shows the shortcuts. (Joshua Goins, kirigami MR #2040)

Gear 26.04.0

Setting up a Samba share for one of your folders so people can connect to it over the network now turns on the Samba service (on systemd-based distros) if needed. This completes the project to make Samba sharing relatively painless! (Thomas Duckworth, KDE Bugzilla #466787)

Notable Bug Fixes

Plasma 6.5.6

Monitor names shown in the Brightness & Color widget now update as expected if you connect or disconnect them while the system is asleep. (Xaver Hugl, KDE Bugzilla #495223)

Fixed multiple issues that caused custom-tiled windows on screens that you disconnect to move to the wrong places on any of the remaining screens. (Xaver Hugl, kwin MR #7999)

Plasma 6.6.0

Hardened KWin a bit against crashing when the graphics driver resets unexpectedly. (Vlad Zahorodnii, kwin MR #8769)

Fixed a case where Plasma could crash when used with the i3 tiling window manager. (Tobias Fella, KDE Bugzilla #511428)

Fixed a potential “division by 0” issue in system monitoring widgets and apps that messed up the display percentage of Swap sensors on systems with no swap space. (Kartikeya Tyagi, libksysguard MR #462)

Worked around a Wayland bug (yes, an actual Wayland bug — as in, a bug in one of its protocol definitions!) related to input method key repeat. Why work around the bug instead of fixing it? Because it’s already fixed in a newer version of the protocol, but KWin needs to handle apps that use the old version, too. (Xuetian Weng, kwin MR #8700)

Unified the appearance of HDR content in full-screen windows and windowed windows. (Xaver Hugl, KDE Bugzilla #513895)

Fixed a layout glitch in the System Tray caused by widgets that include line breaks (i.e. \n characters) in their names. (Christoph Wolk, KDE Bugzilla #515699)

The Web Browser widget no longer incorrectly claims that every page you visit tried to open a pop-up window. (Christoph Wolk, kdeplasma-addons MR #1003)

Fixed a layout glitch in the Quick Launch widget’s popup. (Christoph Wolk, kdeplasma-addons MR #1004)

You can now launch an app in your launcher widget’s favorites list right after overriding its .desktop file; no restart of plasmashell is required anymore. (Alexey Rochev, KDE Bugzilla #512332)

Fixed an issue that made inactive windows dragged from their titlebars get raised even when explicitly configured not to raise in this case. (Vlad Zahorodnii, KDE Bugzilla #508151)

Plasma 6.6.1

When a battery-powered device is at a critically low power level, putting it to sleep and charging it to a normal level no longer makes it incorrectly run the “oh no, I’m critically low” action immediately after it wakes up. (Michael Spears, powerdevil MR #607)

The overall app ratings shown in Discover now match a simple average of the individual ratings. (Akseli Lahtinen, KDE Bugzilla #513139)

Searching for Activities using KRunner and KRunner-powered searches now works again. (Simone Checchia, KDE Bugzilla #513761

Frameworks 6.24

Worked around a Qt bug that caused extremely strange cache-related issues throughout Plasma and Kirigami-based apps that would randomly break certain components. (Tobias Fella, kirigami MR #2039)

Notable in Performance & Technical

Plasma 6.6.0

Added support for setting custom modes for virtual screens. (Xaver Hugl, kwin MR #8766)

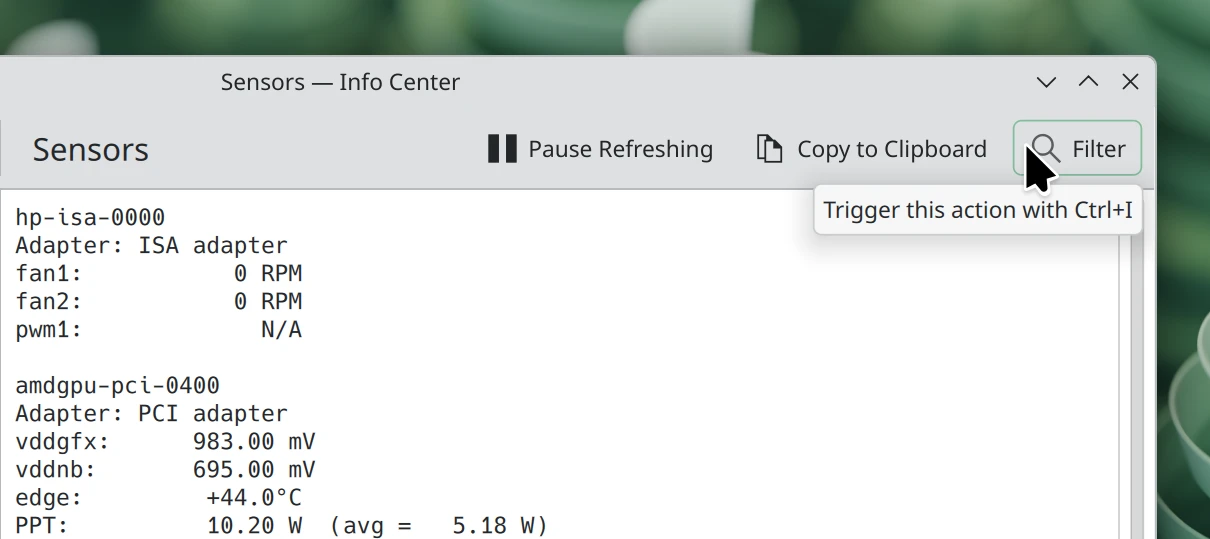

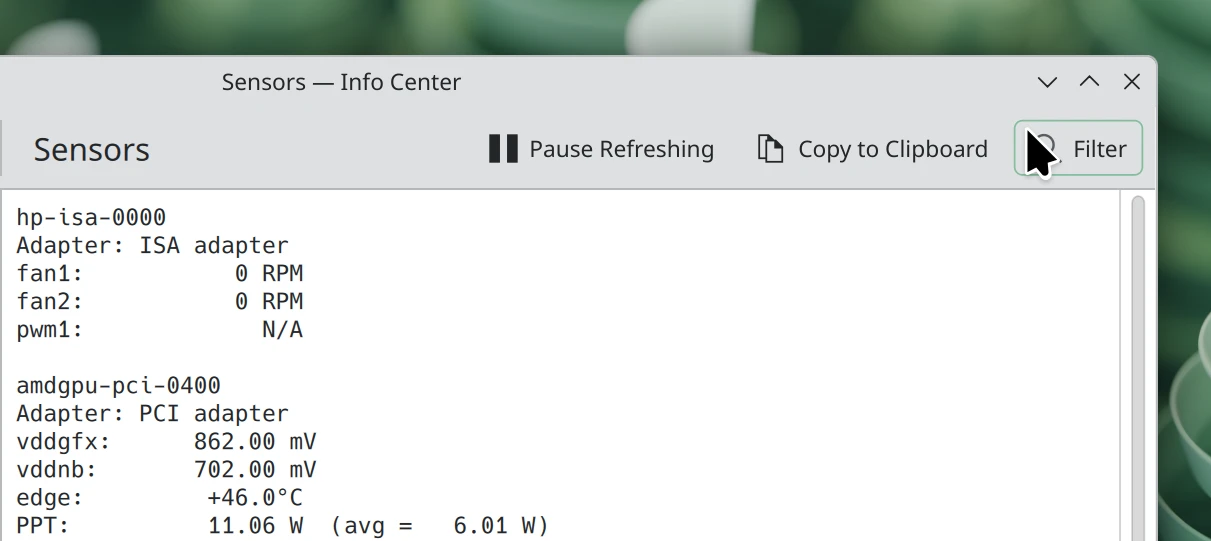

Added GPU temperature monitoring support for additional GPUs. (Barry Strong, ksystemstats MR #123)

Plasma 6.7.0

Scrolling in scrollable views spawned by KWin (not Plasma, just KWin itself) no longer goes 8 times slower than it ought to. Thankfully there are very few such views, so almost nobody noticed the issue. However fixing it facilitates adding a “scroll to switch virtual desktops” feature to the Overview effect for Plasma 6.7! (Kai Uwe Broulik, kwin MR #8800)

Frameworks

Moving a file to the trash is now up to 50 times faster and more efficient. (Kai Uwe Broulik, kio MR #2147)

How You Can Help

KDE has become important in the world, and your time and contributions have helped us get there. As we grow, we need your support to keep KDE sustainable.

Would you like to help put together this weekly report? Introduce yourself in the Matrix room and join the team!

Beyond that, you can help KDE by directly getting involved in any other projects. Donating time is actually more impactful than donating money. Each contributor makes a huge difference in KDE — you are not a number or a cog in a machine! You don’t have to be a programmer, either; many other opportunities exist.

You can also help out by making a donation! This helps cover operational costs, salaries, travel expenses for contributors, and in general just keep KDE bringing Free Software to the world.

To get a new Plasma feature or a bug fix mentioned here

Push a commit to the relevant merge request on invent.kde.org.

Hey everyone!

I am Siddharth Chopra, a second year engineering student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee. I'm really excited to be working on Marknote as a part of the Season of KDE program this year, under the mentorship of Carl Schawn.

Marknote, as it is aptly named, is KDE's own markdown based note taking app. The aim of my project is to improve Marknote by adding the much requested source mode, alongside other enhancements.

Progress so far

3 weeks into the project, I have been successful in adding a working source mode functionality to the editor. When source mode is activated, the contents of the source markdown file are allowed to be edited directly, instead of showing the rendered markdown. This is incredibly useful, in cases where the user needs manual control over the contents of the note, or in case there is some glitch in the rendering (which unfortunately still happens often).

Demo Video

Technical Roadmap & Challenges

The main editor of Marknote comes from the file EditPage.qml. As part of my initial approach, I added a global property here to check if source mode was enabled, and then conditionally changed components of this editor. Although this worked, but it brought along some of its own issues. First of all it made the code unnecessarily complex. It also meant that components like the formatting bar now needed to be repurposed to work with source mode, which is a challenge in itself.

So, my mentor suggested to move the raw editor into a new file, to keep the code maintainable. This led to the original EditPage being split into RichEditPage and RawEditPage. Similarly, the respective backends were also split in two, as the needs of both the editors are significantly distinct.

Additionally, I had to consider specially the source mode for images. Because when loaded, image URL's are not kept intact, instead they are replaced with a hash, that maps to the image in memory. Also, the editor internally uses html for rendering images, which I also had to convert back to markdown for source mode.

And someone who is not a designer by any means, deciding the form and placement of the mode toggle button was in itself a mini lesson in UI design ;) Initially I went with a toggle switch. But when I shared that for feedback, I learnt that a checkable button is the ideal UI element here.

Future Plans

My proposal mentions features apart from the source mode, which I plan to complete. While working on the current feature, I noticed multiple bugs in the app, which I intend to fix as well.

Overall experience

It has been a great experience working with the KDE community, and really exciting to be able to contribute to an app that so many users around the world use every day! I would also like to express my gratitude towards my mentor, for being there for whatever issue I faced!

Friday, 13 February 2026

Let’s go for my web review for the week 2026-07.

The Media Can’t Stop Propping Up Elon Musk’s Phony Supergenius Engineer Mythology

Tags: tech, politics, journalism, business

There’s really a problem with journalism at this point. How come when covering the tech moguls they keep leaving out important context and taking their fables at face value?

https://karlbode.com/the-press-is-still-propping-up-elon-musks-supergenius-engineer-mythology/

But they did read it

Tags: tech, literature, scifi, business, politics

Indeed, don’t assume they misunderstood the sci-fi and fantasy they read and you know. Clearly they just got different opinions about it because their incentives and world views are different from your.

https://tante.cc/2026/02/12/but-they-did-read-it/

Microsoft’s AI-Powered Copyright Bots Fucked Up And Got An Innocent Game Delisted From Steam

Tags: tech, game, dmca, copyright, law

Automated DMCA take downs have been a problem for decades now… They still bring real damage, here is an example.

Launching Interop 2026

Tags: tech, web, browser, interoperability

This is a very important initiative. For a healthy web platform we need good interoperability between the engines. I’m glad they’re doing it again.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2026/02/launching-interop-2026/

How I built Fluxer, a Discord-like chat app

Tags: tech, foss, messaging

Clearly early days… Could that become a good place to land for people fleeing off Discord?

https://blog.fluxer.app/how-i-built-fluxer-a-discord-like-chat-app/

New And Upcoming IRCv3 Features

Tags: tech, messaging, irc

It’s nice to still see some activity around IRC.

https://libera.chat/news/new-and-upcoming-features-3

Uses an ESP8266 module and an Arduino sketch to display the local time on a inexpensive analog quartz clock

Tags: tech, hardware, embedded, ntp, time

This is definitely a cool hack. Now I feel like doing something like this to every clock I encounter.

https://github.com/jim11662418/ESP8266_WiFi_Analog_Clock

LLVM: Concerns about low-quality PRs beeing merged into main

Tags: tech, ai, machine-learning, copilot, foss, codereview

Clearly Free Software projects will have to find a way to deal with LLM generated contributions. A very large percentage of them is leading to subtle quality issues. This also very taxing on the reviewers, and you don’t want to burn them out.

https://discourse.llvm.org/t/concerns-about-low-quality-prs-beeing-merged-into-main/89748

An AI Agent Published a Hit Piece on Me

Tags: tech, ai, machine-learning, copilot, foss, commons

I guess when you unleash agents unsupervised their ethos tend to converge on the self-entitled asshole contributors? This raise real questions, this piece explains the situation quite well.

https://theshamblog.com/an-ai-agent-published-a-hit-piece-on-me/

Spying Chrome Extensions: 287 Extensions spying on 37M users

Tags: tech, browser, security, attention-economy, spy

Oh this is bad! The amount of data exfiltrated by those malicious extensions. Data brokers will do anything they can to have something to resell. This is also a security and corporate espionage hazard.

https://qcontinuum.substack.com/p/spying-chrome-extensions-287-extensions-495

ReMemory - Split a recovery key among friends

Tags: tech, tools, security

Accidents can happen in life. This might come in handy if you loose memory for some reason. It requires planning ahead though.

https://eljojo.github.io/rememory/

Penrose

Tags: tech, tools, data-visualization

Looks like a nice option for visualisations.

Boilerplate Tax - Ranking popular programming languages by density

Tags: tech, programming, language, statistics, type-systems

Interesting experiment even though some of the results baffle me (I’d have expected C# higher in the ranking for example). Still this gives some food for thought.

https://boyter.org/posts/boilerplate-tax-ranking-popular-languages-by-density/

The cost of a function call

Tags: tech, c++, optimisation

If you needed a reminder that inlining functions isn’t necessarily an optimisation, here is a fun little experiment.

https://lemire.me/blog/2026/02/08/the-cost-of-a-function-call/

It’s all a blur

Tags: tech, graphics, blur, mathematics

Wondering if blurs can really be reverted? There’s some noise introduced but otherwise you can pretty much reconstruct the original.

https://lcamtuf.substack.com/p/its-all-a-blur

Simplifying Vulkan One Subsystem at a Time

Tags: tech, graphics, vulkan, api, complexity

There are lessons and inspirations to find in how the Vulkan API is managed. The extension system can be unwieldy, but with the right approach it can help consolidate as well.

https://www.khronos.org/blog/simplifying-vulkan-one-subsystem-at-a-time

What Functional Programmers Get Wrong About Systems

Tags: tech, data, architecture, system, type-systems, functional, complexity

Interesting essay looking at how systems evolve their schemas over time. We’re generally ill-equipped to deal with it and this presents options and ideas to that effect. Of course, the more precise you want to be the more complexity you’ll have to deal with.

Modular Monolith and Microservices: Modularity is what truly matters

Tags: tech, architecture, modules, microservices, services, complexity

No, modularity doesn’t imply micro services… You don’t need a process and network barrier between your modules. This long post does a good job going through the various architecture options we have.

https://binaryigor.com/modular-monolith-and-microservices-modularity-is-what-truly-matters.html

Using an engineering notebook

Tags: tech, engineering, note-taking, memory, cognition

I used to do that, fell into the “taking notes on the computer”. And clearly it’s not the same, I’m thinking going back to paper notebooks soon.

https://ntietz.com/blog/using-an-engineering-notebook/

On screwing up

Tags: tech, engineering, organisation, team, communication, failure

Everyone makes mistakes, what matters is how you handle them.

https://www.seangoedecke.com/screwing-up/

Why is the sky blue?

Tags: physics, colors

Excellent piece which explains the physics behind the atmospheric colours. Very fascinating stuff.

https://explainers.blog/posts/why-is-the-sky-blue/

Bye for now!

Friday, 13 February 2026

KDE today announces the release of KDE Frameworks 6.23.0.

This release is part of a series of planned monthly releases making improvements available to developers in a quick and predictable manner.

New in this version

Baloo

- [IndexCleaner] Use one transaction for each excludeFolder during cleanup. Commit.

- [Extractor] Split long extraction runs into multiple transactions. Commit.

- [Extractor] Release DB write lock while content is extracted. Commit.

- [Benchmarks] Replace QTextStream::readLine with QStringTokenizer. Commit.

- [Benchmarks] Verify /proc open result for IO stats. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- [Engine] Replace remaining raw PostingIterator* with unique_ptr. Commit.

- [SearchStore] Replace raw PostingIterator* with unique_ptr. Commit.

- [PostingIterator] Clean up unused headers. Commit.

- [AdvancedQueryParser] Use categorized logging for debug message. Commit.

- [Transaction] Fix invalid qWarning macro usage. Commit.

- Use categorized logging in priority setup code. Commit.

- Clean up priority setup code. Commit.

- [baloo_file] Use categorized logging for warnings. Commit.

- [QueryTest] Fix leak of iterator returned from executed query. Commit.

- [Engine] Fix possible memory leaks in PhraseAndIterator. Commit.

- [Engine] Fix possible memory leaks in {And,Or}PostingIterator. Commit.

- [FileIndexScheduler] Emit correct state on startup. Commit.

- [FileIndexScheduler] Simplify startup/cleanup logic. Commit.

- [IndexerConfig] Properly deprecate obsolete API. Commit.

- [BalooSettings] Enable Notifiers for changes. Commit.

- [FileIndexerConfig] Move filter update to constructor. Commit.

- [balooctl] Minor config command output cleanup, fix error message. Commit.

- [PendingFile] Add proper debug stream operator. Commit.

- [PendingFile] Inline trivial internal method. Commit.

- Use Baloo namespace for KFileMetadata::ExtractionResult specialization. Commit.

Breeze Icons

- Add update-busy status icon. Commit.

- Make base 22px globe icon symbolic. Commit.

- QrcAlias.cpp - pass canonical paths to resolveLink. Commit.

- Make the non-symbolic version of globe icon to be colorful. Commit.

- Create symbolic version for preferences-system-network. Commit.

- Enable LSAN for leak checking. Commit.

- Fix kdeconnect-symbolic icons not being color-aware. Commit.

- Properly resolve links for the resources. Commit.

Framework Integration

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KArchive

- K7ZipPrivate::folderItem: Limit the amount of folderInfos to a "reasonable" amount. Commit.

- 7zip: defines to constexpr (or commented out if unused). Commit.

- 7zip: make it clear we only support an int number of files. Commit.

- 7zip: convert a bunch of int to qsizetype. Commit.

- 7zip: Remove unused defines. Commit.

- 7zip: Add names to function parameters. Commit.

- 7zip: Use ranges::any_of. Commit.

- 7zip: Convert loops into range-for loops. Commit.

- 7zip: Add [[nodiscard]]. Commit.

- 7zip: Mark 3 qlist parameters as const. Commit.

- 7zip: Mark sngle argument constructors as explicit. Commit.

- 7zip: Use "proper" C++ include. Commit.

- 7zip: Remove unused BUFFER_SIZE. Commit.

- 7zip: Use default member initializer. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- KLimitedIODevice: mark two member variables as const. Commit.

- Kzip: Bail out if the reported size of the file is negative. Commit.

- Fix OSS-Fuzz AFL builds. Commit.

KBookmarks

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KCodecs

- Protect against null bytes in RFC 2047 charsets. Commit.

- Remove a few temporary allocation on RFC 2047 decoding. Commit.

- [KEndodingProber] Drop broken and irrelevant ISO-2022-CN/-KR detectors. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Remove disabled, obsolete GB2312 data. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Reduce packed model data boilerplate. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Replace pack/unpack macros with constexpr functions. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Add tests for ISO-2022-JP and HZ encoding. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Remove unused byte pos member from CodingStateMachine. Commit.

- [KEncodingProber] Add prober benchmarks. Commit.

- Fix quadratic complexity when searching for the encoded word end. Commit.

- Use QByteArrayView. Commit.

- Don't detach encoded8Bit during encoding. Commit.

- Fix OSS-Fuzz AFL builds. Commit.

KColorScheme

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KConfig

- Kconfigwatcher: prevent a QThreadLocal to be creatde when exiting. Commit.

- Fix macos standard shortcut conflicts. Commit. Fixes bug #512817

- Kconfigwatcher: Add context argument to connect. Commit.

- Kconfigskeletontest: Fix memory leak. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- KConfigIni: parseConfig simplify implementation. Commit.

- Doc: KConfig: update link introduction. Commit.

- KConfig: better handle Anonymous case. Commit.

- Autotests/qiodevice: add a test for the QFile case. Commit.

- Kconfig_target_kcfg_file: use newer built-in cmake code to create kcfgc file. Commit.

- Kconfigxt: Add KCONFIG_CONSTRUCTOR option. Commit.

- Kconfigskeleton: Add ctor using std::unique_ptr

. Commit. - Kconfig: support passing in a QIODevice. Commit.

KDBusAddons

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KDeclarative

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KDE Daemon

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KGlobalAccel

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KGuiAddons

- Add Android support for idle inhibition. Commit.

- WaylandClipboard: fix pasting text when QMimeData also has an image. Commit. Fixes bug #513701

- Add KSystemInhibitor as frontend to the xdg-desktop-portal inhibition system. Commit.

- Restore building with wayland < 1.23.0. Commit.

- Ksystemclipboard: Check m_thread in destructor. Commit. Fixes bug #514512

- Examples/python: add an example for KSystemClipboard. Commit.

- Python: fix crash when using KSystemClipboard::setMimeData. Commit.

- Python: specify enum type for KKeySequenceRecorder::Pattern. Commit.

- KImageCache: make findPixmap destination QPixmap have alpha channel if inserted QPixmap had alpha channel. Commit.

- Add another explicit moc include to source file for moc-covered header. Commit.

KImageformats

- Fix oss-fuzz AFL build (again). Commit.

- Fix OSS-Fuzz AFL builds. Commit.

- Text -> test. Commit.

- IFF: add uncompressed RGFX support. Commit.

- IFF: add CD-i Rle7 support. Commit.

- Decode Atari ST VDAT chunks. Commit.

- IFF: add support for CD-i YUVS chunk (and minor code improvements). Commit.

- Add support for CD-I IFF images. Commit.

- Add JXL testfile which previously triggered crash. Commit.

- Jxl: fix crash on lossy gray images. Commit.

- Add gray AVIF files with various transfer functions. Commit.

- Avif: Improved color profiles support. Commit.

KIO

- Add missing since documentation. Commit.

- Add ThumbnailRequest::maximumFileSize. Commit.

- KFilePlacesEventWatcher: Set drag disabled on invalid index and on headers. Commit. Fixes bug #499952

- Fileundomanager: prevent mem leak upon destruction. Commit.

- Core/ListJob: add list Flags ExcludeDot, ExcludeDotDot. Commit.

- Dropjob: add DropJobFlag::ExcludePluginsActions flag support. Commit. See bug #509231. Fixes bug #514697

- DropJob: Polish QMenu before creating native window. Commit.

- Tests: kfilewidgetttest in dropfiles make sure to clean up QMimeData*. Commit.

- FilePreviewJob: Let StatJob resolve symlinks. Commit.

- DropJob: Use CommandLauncherJob for drop onto executable. Commit.

- RenameDialog: Also show file item metadata when thumbnail failed. Commit.

- Dropjob: handle drop from Places View properly. Commit. See bug #509231. Fixes bug #514697

- PreviewJob: Ignore ERR_INTERNAL. Commit.

- KFilePlacesView: better compute the maximum size of icon tolerable. Commit.

- KFileWidget: When navigator loses focus, apply the uncommittedUrl to navigator. Commit.

- RenameDialog: Use size and mtime from preview job stat, too. Commit.

- Listjob: use modern for loop. Commit.

- Listjob: reduce nesting in recurse function. Commit.

- Listjob: split listing entries into a filter and a recurse function. Commit.

- RenameDialog: Fix grammar by adding a comma. Commit.

- Fix binary compatibility. Commit.

- Tests/kfilewidgettests: add command line args the open test. Commit.

- KFilePreviewGenerator: pass dpi to the PreviewJob. Commit. Fixes bug #489298

- Kmountpoint: use statx to get device id. Commit.

- KFileItemActions: Add "Run Executable" action for executable files. Commit.

- Udsentry: add documentation for UDS_SUBVOL_ID. Commit.

- Kioworkertest: add UDS_MOUNT_ID output for stat. Commit.

- StatJob: add StatMountId to retrieve unique mount id. Commit.

- KFilePlacesModel: Add placeCollapsedUrl. Commit.

- FilePreviewJob: Set job error, if applicable. Commit.

- KDirOperator: implement single tap gesture. Commit. Fixes bug #513606

- KCoreDirLister: Add parentDirs of dirs that have not been deleted to pendingUpdates list. Commit. Fixes bug #497259

- KMountpoint: remove redundant code, and reuse a function. Commit.

- PreviewJob: prevent potential crash when FilePreviewJob yields results sync. Commit.

- PreviewJob: estimate device ids first. Commit.

- KDirModel/KFileWidget: Use relative date formatting for Modified field. Commit.

- Listjob: replace misleading comment about repeated key lookups. Commit.

- Stat_unix: document that statx(dirfd wouldn't be any faster. Commit.

- Kioworkers/file: check temp file opening result. Commit.

- Autotests: fix unused warnings. Commit.

- KUrlNavigatorButton: Don't set a button icon. Commit.

- Kioworkertest: add subvolId output for stat. Commit.

- StatJob: add StatSubVolId to retrieve btrfs/bcachefs subvol number. Commit.

- Job: improve property management performance. Commit.

- Job: update mergeMetaData code to be more modern + comment. Commit.

- Udsentry: improve operator>> performance. Commit.

- KPropertiesDialog: Remove unused variable. Commit.

- PreviewJobPrivate: remove unused method declaration. Commit.

- Use QList::takeFirst instead of QList::front & QList::pop_front. Commit.

- PreviewJob: dissolve struct PreviewItem, serves no extra purpose. Commit.

- FilePreviewJob::item(): return const ref to KFileItem directly, by only use. Commit.

- PreviewJob: introduce internal struct PreviewSetupData, to group related data. Commit.

- PreviewJob: introduce internal struct PreviewOptions, to group related data. Commit.

- PreviewJobPrivate: rename determineNextFile to startNextFilePreviewJobBatch. Commit.

- PreviewJob: create PreviewItem instance on-the-fly. Commit.

- PreviewJobPrivate: rename member initialItems to fileItems. Commit.

Kirigami

- ToolbarLayout: Don't draw frames with an empty toolbar. Commit. Fixes bug #512396

- Make the global background actually invisible. Commit.

- Enable back button on first page in RTL. Commit. Fixes bug #511295

- ActionToolBar: fix actions showing both in toolbar and in hidden actions menu. Commit.

- Add new Kirigami logo. Commit.

- Revert "Temporarily drop test case that is broken with Qt 6.11". Commit.

- MnemonicAttached: move to primitives. Commit.

- Fix inline drawers in RTL layout. Commit.

- Do an opacity animation for the menu layers. Commit.

- GlobalDrawer: default size according to contents. Commit. Fixes bug #505693

- SelectableLabel: don't break coordinates of global ToolTip instance. Commit. Fixes bug #510860. Fixes bug #511875

- Controls/SwipeListItem: fix action positions in RtL. Commit.

- ShadowedRectangle: Improve visuals when blending a texture. Commit.

- Make types more explicit for tooling. Commit.

- Make action handling linter-friendly. Commit.

- Templates/private: fix qmldir. Commit.

- Placeholdermessage: don't bind maximum to explicit width. Commit.

- PlaceholderMessage: handle unusually long text better. Commit. Fixes bug #514164

- BannerImage: Don't shadow implicitWidth property. Commit.

- Fix Android icon bundling. Commit.

KItemViews

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KJobWidgets

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KNotifications

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KNotifyConfig

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KStatusNotifieritem

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KTextEditor

- Some tests for setVirtualCursorPosition. Commit.

- Add small test for virtual column conversions. Commit.

- Fix fromVirtualColumn. Commit.

- Proper handling of tabs in virtual cursor setting. Commit. Fixes bug #513898

- Proper handling of tabs in virtual cursor setting. Commit. Fixes bug #513898

- Handle any unicode newline sequence during paste. Commit.

- Fix typo. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- Avoid to leak ranges. Commit.

- Don't leak memory. Commit.

- Don't leak a cursor. Commit.

- Ensure we call the cleanups. Commit.

- Don't leak cursors. Commit.

- Fix leaking of completion moving ranges. Commit.

- We re-parent this, use a QPointer to be sure we know if that is still alive. Commit.

- Fix leak in TextBuffer::balanceBlock. Commit.

- Don't leak cursor and range. Commit.

- Avoid to leak the document. Commit.

- Don't leak cursors & ranges. Commit.

- Fix memleak in vi mode mark handling. Commit.

- Don't leak the mainwindow. Commit.

- Ensure the document dies with the toplevel widget. Commit.

- Avoid to leak doc in some tests. Commit.

- Fix memleak in KateLineLayoutMap. Commit.

- Don't leak the document in some tests. Commit.

- Avoid to leak memory in testing. Commit.

- Disable CamelCursor by default. Commit.

- Fix since 6.23 & comments. Commit.

- Docs: Mention that code folding highlight is also disabled. Commit.

- Move bracket highlight suppression to view update logic. Commit.

- Add option to disable bracket match highlight when inactive. Commit.

- Clear m_speechEngineLastUser early to avoid that it is used in error handling for speechError. Commit. Fixes bug #514375

KTextWidgets

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KUserFeedback

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

KWidgetsAddons

- KPageView: Check for valid indices during list search. Commit. Fixes bug #496143

- Kactionmenu: Use delegating constructor. Commit.

- Add test for KActionMenu. Commit.

- Clean up touch device in tests. Commit.

- Kpageview: Don't leak NoPaddingToolBarProxyStyle. Commit.

- Kacceleratormanagertest: Don't leak action. Commit.

- KCollapsibleGroupBox: Fix arrow indicator not updating immediately. Commit.

KXMLGUI

- Avoid toLower, use case insensitive comparison. Commit.

- De-duplicate case insensitive string equality functions. Commit.

- Fix memory leaks in unit tests. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- Drop (wrong kind of) asserts in KToolTipHelperPrivate code. Commit.

- Replace pointer with optional. Commit.

- Replace simple slot with lambda. Commit.

- Remove pointless QKeySequence->QVariant conversion. Commit.

- Use raw pointers for some commonly used classes's pimpl pointer. Commit.

Prison

- Consistently namespace ZXing version defines. Commit.

- Remove workarounds for ZXing 3.0 not having bumped its version yet. Commit.

- Adapt to more ZXing 3.0 API changes. Commit.

- Actually search for ZXing 3. Commit.

- Fix build without ZXing. Commit.

- Support ZXing 3 for barcode generation. Commit.

- Auto-detect text vs binary content for GS1 Databar barcodes. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- Adapt barcode scanner to ZXing 3 changes. Commit.

- Port away from deprecated ZXing API. Commit.

QQC2 Desktop Style

- Menu: Calculate implicitHeight from visibleChildren. Commit. Fixes bug #515602

- ItemDelegate: Give a bigger padding to the last item. Commit. Fixes bug #513459

- Combobox: use standard menu styling for popup. Commit. See bug #451627

- SearchField: add manual test. Commit.

- Add SearchField. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- Kquickstyleitem: Avoid divide by zero. Commit.

Solid

- Fix(fstab): Return valid URLs for NetworkShare for smb mountpoints. Commit.

- Documentation fixes. Commit.

- Add displayName() implementation to UDev backend with vendor/product deduplication. Commit.

- Extract vendor/product fallback logic into reusable utility function. Commit.

- Improve device vendor/product lookup with hwdb fallback. Commit.

- [UdevQt] Reduce allocations in decodePropertyValue helper. Commit.

- Free lexer-allocated data also when parsing fails. Commit.

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

- Use delete instead of deleteLater() when DevicePrivate refcount drops to 0. Commit. Fixes bug #513508. Fixes bug #494224. Fixes bug #470321. Fixes bug #513089. Fixes bug #513921

- Avoid crash on device removal. Commit. Fixes bug #514791

- Add missing ejectRequested to OpticalDrive interface. Commit.

- Add missing override in winopticaldrive. Commit.

- Add missing signals to StorageAccess backends. Commit. Fixes bug #514176

- Add missing overrride in winstorageaccess. Commit.

- Fix macOS build: Replace make_unique with explicit new for private IOKitDevice constructor. Commit.

- Use more precise type for m_reverseMap. Commit.

- Replace _k_destroyed slot with lambda. Commit.

- Don't call setBackendObject() in DevicePrivate dtor. Commit.

- Remove unneeded intermediate variables. Commit.

- Manage backend object using unique_ptr. Commit.

- Remove unneeded destroyed handling for backend object. Commit.

- Manage DeviceInterface using unique_ptr. Commit.

- Devicemanager: remove unused includes. Commit.

Syndication

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

Threadweaver

- Enable LSAN in CI. Commit.

This release brings improvements to generators, better build system integration and several bugfixes.

As always, big thanks to everyone who reported issues and contributed to QCoro. Your help is much appreciated!

Directly Awaiting Qt Types in AsyncGenerator Coroutines

The biggest improvement in this release is that QCoro::AsyncGenerator coroutines now support

directly co_awaiting Qt types without the qCoro() wrapper, just like QCoro::Task coroutines

already do (#292).

Previously, if you wanted to await a QNetworkReply inside an AsyncGenerator, you had to

wrap it with qCoro():

QCoro::AsyncGenerator<QByteArray> fetchPages(QNetworkAccessManager &nam, QStringList urls) {

for (const auto &url : urls) {

auto *reply = co_await qCoro(nam.get(QNetworkRequest{QUrl{url}}));

co_yield reply->readAll();

}

}

Starting with QCoro 0.13.0, you can co_await directly, just like in QCoro::Task:

QCoro::AsyncGenerator<QByteArray> fetchPages(QNetworkAccessManager &nam, QStringList urls) {

for (const auto &url : urls) {

auto *reply = co_await nam.get(QNetworkRequest{QUrl{url}});

co_yield reply->readAll();

}

}

Other Features and Changes

- Generator’s

.end()method is nowconst(andconstexpr), so it can be called on const generator objects (#294). GeneratorIteratorcan now be constructed in an invalid state, allowing lazy initialization of iterators (#318).qcoro.hnow only includes QtNetwork and QtDBus headers when those features are actually enabled, resulting in cleaner builds when optional modules are disabled (#280).

Bugfixes

- Fixed memory leak in QFuture coro wrapper when a task is destroyed while awaiting on a QFuture (#312, Daniel Vr√°til)

- Fixed include paths when using QCoro with CMake’s FetchContent (#282, Daniel Vr√°til; #310, Nicolas Fella)

- Fixed QCoroNetworkReply test on Qt 6.10 (#305, Daniel Vr√°til)

Full changelog

Support

If you enjoy using QCoro, consider supporting its development on GitHub Sponsors or buy me a coffee on Ko-fi (after all, more coffee means more code, right?).

Thursday, 12 February 2026

The world of free and open-source software (FOSS) is full of big-hearted, altruistic people who love serving society by giving away their labor for free. It’s incredible. These folks are supporting so many people by providing the world with high quality free software, including in KDE, my FOSS community of choice.

But while they do it, who’s supporting them? We don’t talk about this as much.

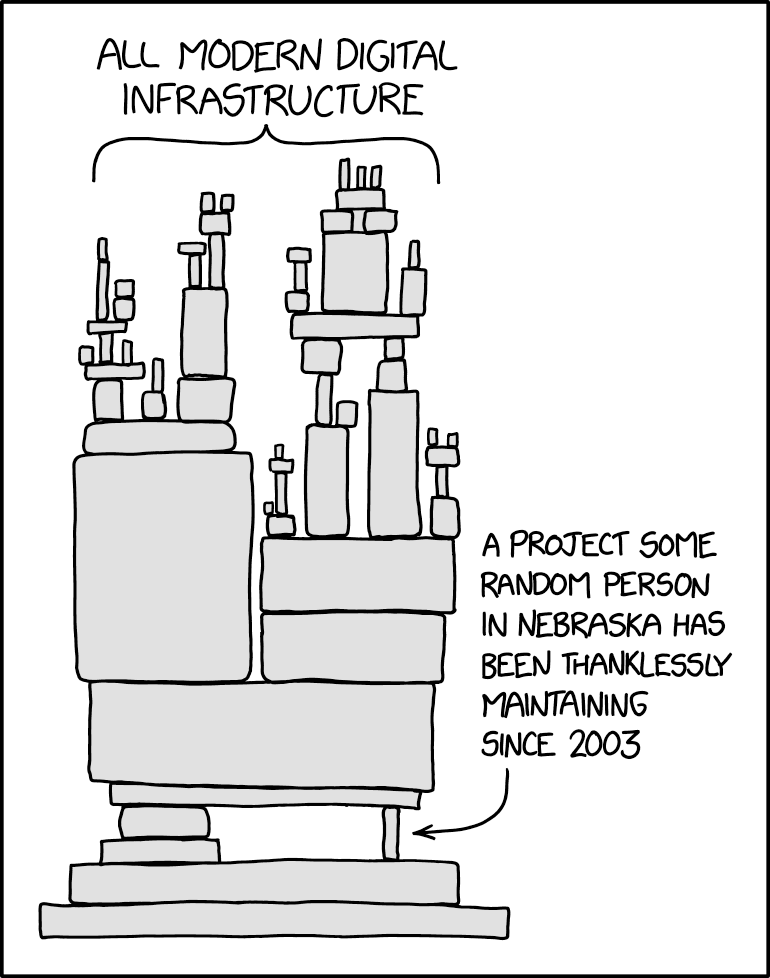

A recent Reddit post by a volunteer developer burning out reminded me of the topic, and it’s not the first one. Denis Pushkarev of core-js wrote something similar in 2023, and we’re probably all familiar with this XKCD comic:

The topic is also not limited to the FOSS world; it’s broadly applicable to all volunteer activities. Can’t feed the homeless in a soup kitchen if you’re sick and sneezing into the soup! Can’t drive to the library to teach adult reading classes if your car’s broken down.

In order to support others, you need support yourself! Who can provide that support? Here are a bunch of cases that work:

- Yourself in the present (with a job — related or unrelated to your FOSS work)

- Yourself in the past (retired)

- Your partner in the present (married to a primary or sole income-earner)

- Your partner in the past (partner left you lots of money after death or divorce)

- Your parents in the present (you’re their dependent)

- Your parents in the past (born rich or received a big inheritance later)

- The state (disabled, a student, or on a similar program)

All these cases work. They provide enough money to live, and you still get to work on FOSS!

There are lots of other good options, but here are some of the bad ones that don’t work:

- Other people via donations: you never get enough donations, and if you put the effort into fundraising required to make it work, that becomes your job.

- Yourself in the future: if you’re living off loans, you’re screwing over future you!

- Nobody: if you’re eating up your savings, you’ll eventually run out of money and be destitute. If you’re fortunate enough to live in a place where “The state” is an option, it will be at a diminished standard of living.

We must always answer for ourselves the question of how we’re going to be supported while we continue to contribute to the digital commons. If you don’t do it for a living, it’s a critically important question. Never let anyone guilt-trip you into doing volunteer work you don’t have the time or money for! It’s a sure road to burnout or worse.

Airplane safety briefings tell people to “put on your mask before helping others.” Why? Same reason as what we’re talking about here: you can’t support others if you’re not first supported yourself. If you try, you’ll fail, either immediately, or eventually. You must be properly supported yourself before you can be of use to others.

We are happy to announce the release of Qt Creator 19 Beta2.

soumyatheman

soumyatheman @soumyatheman:matrix.org

@soumyatheman:matrix.org GSoC

GSoC

ngraham

ngraham